The fan

08.05.2016Impossible to unfurl – or unfold – the whole history of the fan. Probably because it wasn’t always folding. The Eureka moment first came when man watched a bird’s wings flapping in the air. And from this, a myriad of uses for fans were born, from the frivolous to the practical, as fans induce airflow that can be as cool as hot.

In Hindi, a fan is called a « pankha », and « pankh » means the feather of a bird. A few wing beats north to China and the Chinese sign for fan means « feather under a roof ». As a natural miming process, you could say that the action of agitating the air using a flat surface to stoke fires, repel insects and cool oneself down probably arrived pretty early on in the story of mankind and in the home environment. The Mayas, African Kings, Greeks, Romans and Etruscans all invented their versions of fans. The oldest preserved fans were found in the tomb of Emperor Mawangdui (IInd century BC) in Hunan in China. But painted fans also appeared in Egyptian tombs dating back to the third millennium BC, when the job of servitor to the Pharaoh – wielding a fabellum, a long handled fan of feathers – to keep him cool was deemed a highly prestigious profession. The fan symbolised « Chou », the fertile power of wind rustling across the ground.

Surprisingly, even though a fan only wafts air, it has always been an accessory of those in power. Pharaohs, emperors, kings and queens, popes – until 1975 – great wizards and other moguls, all the great and good needed fanning. Then, right at the other end of the historical timeline, the fan became an item of coquetry, a tool used by the seductress to enhance her aura of mystery and function as the conduit for her assent or reluctance. Until the next instruction, via the fan.

But it was in Japan that the modern fan took flight. The fan came to the island via China. They folded it: literally and figuratively, with art, giving it many uses. The fixed (or flat) fan, « ushiwa », was useful in the kitchen for example. But the folding fan or « ôgi » was used during the Middle Ages as part of the complex rituals of gallantry amongst the working classes, finding its way into the narrative gestures of Nô and Kabuki theatre, and entering dance and martial arts as it had previously done in China. The greatest painters have honed their artistic endeavours on fan leaves. There is even a war fan used by the Shogun called the « gunsen » with steel mounts, white leaves and a red circle in the centre. Folding fans are still very common in Asian culture.

Portuguese settlers brought the fan to Europe in the XVIth century. From the markets in Lisbon to thrones and crowns, the fan became a unique ceremonial and leisure accessory, especially in French and Italian craft traditions. It was Catherine de Medici, the Queen of France following her marriage to Henri II in 1533, who was credited with making the folding fan popular in France. The great queen Elizabeth of England loved fans so much that she deemed it the only gift she would accept from her subjects. Ladies followed her lead and the fan became all the rage. Its European heyday in Europe was during the XVIIth century. The French Revolution gave it fresh impetus. It experienced a renaissance during the XIXth century mainly thanks to Mr Duvelleroy, until the arrival of the Belle Epoque.

The European history of the folding fan goes on and on… We should take into account some of the details of its construction that make manufacturing fans so tricky: the ribs that form the base upon which the fan leaf is mounted, the slips or reinforced stretch of the ribs, the end section (or arrow), the gorge (section between the head and leaf), the rivet (pin) with its pivot, the head, supportive collar and loop. When ribs are nailed at the base and ribbon detailing is added the fan is called a brisé fan. Each element of the fan is made using rare and delicate materials requiring specific trades such as leather gilders, glove makers, perfumed fan leaf pleaters, fine woodworkers and sometimes even goldsmiths, to name but a few. In the XVIIth century there were lawsuits filed between these trades. It got so bad that Colbert, a minister in Louis XIVs government set up the Guild of Master Fan Makers to control fan making and craftsmanship in 1678 which turned into the Corporation of French Fan makers. These details give an idea of the level of sophistication fans had reached despite their ancient and natural origins.

Fashions fan their own successes: the fan has paid its way in all cultures and across all social divides. However it responds to such an essential gesture, and has courted the interest of craftsmen around the world to such splendid heights, that its existence defies the whims of fashion.

- “Tanagra” (ville de Béotie ayant donné son nom aux statuettes de terre cuite exhumées dans sa nécropole) – Femme coiffée de la Tholia, tenant un éventail, IVe siècle avant Jésus Christ, Musée du Louvre

- Eventail étrusque, Musée archéologique de Florence

- “Tetsu-sen”, Musée de l’Armée (Dist. RMN-Grand Palais) (photo Christophe Chavan)

- Anne D’Autriche (1601-1666), épouse de Louis XIII, Château de Chambord

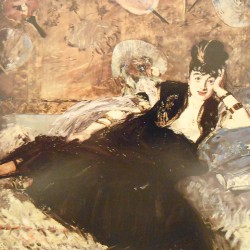

- La Dame aux éventails (Edouard Manet, 1832-1883), Musée d’Orsay

- Portrait de Sarah Bernhardt (Georges Clairin, 1843-1919), Musée du Petit Palais