The gardens of Piet Oudolf

04.03.2017Piet Oudolf is a leading figure in “plant structure/design”. This Dutch horticulturalist is particularly renowned for his urban gardens, including High Line in New York. The success of his gardens propelled the evolution of the “New Perennial Movement” amongst the public.

The “New Perennial Movement” is a concept of plant art initiated by the great Dutch garden landscaper Mien Ruys (1904-1999), whose distant paternity included Irishman William Robinson (1838 -1935) and his friend, the great landscaper Gertrude Jekyll (1843-1932). Ruys loved using perennials (instead of seasonal plants), clearly articulated materials (wood, water, gravel pathways, wooden sleepers) all geometrically laid out and inspired by the simplicity of Japanese gardens; and, more generally, this movement prioritises the natural nature of a garden landscape. Piet Oudolf’s long and creative career expanded this conceptual framework of ecological considerations and a less graphic arrangement of plants that was more natural and adapted to the local biotope.

The internationally renowned horticulturalist published numerous books theorising his research and experimentation to help readers to create their own gardens and understand the author’s particular way of proceeding, in a rigorous yet friendly manner, taking into account the space, position and purpose of the gardens concerned.

Here are some of the key pointers for creating plant structure in a garden. First of all, design a four-season garden that is in tune with its region, using hardy perennial plants that will give structure to the space throughout the year. Then continue with overlapping swathes of plants to create complementary areas, tufts of grasses, tall elements, shrubs, trees… Almost ¾ of the planting should comprise of plants that Oudolf calls “structural”, long season perennials (as they are dubbed by gardeners) because they maintain visual interest through to autumn and even winter; and the remaining ¼ for flowers and foliage (fillers) with colours that bloom for a short period only and not beyond the summer months. The order in which plants are placed should produce visual rhythm by repeating themes (the plants giving the composition structure) that pop up in the distance as a person looks out across the garden or walks around it. Piet Oudolf also mentions the importance of matrix planting using background plants and visually attractive clumps of plants: this matrix should often comprise of tall plants/grasses, especially ones that maintain their presence and density for a long time without having to be replaced or replanted. He recommends using local plants, starting with those that attract bees, birds and butterflies. This natural plant base can be enhanced and contrasted by adding foreign (even exotic) plants as long as they can acclimatise to the location without requiring too much intervention or any specific attention by the gardener concerned. The point is to create a natural, living garden, not a showcase for ephemeral, fragile plants. This space must be designed in tune with the exterior environment that frames it: whether that be a row of trees in a neighbour’s garden, a pathway, buildings, a horizon line, mountains etc. The art of putting the right plants together in beds should be focused on blurring the contours between plants rather than having neatly separated lines of plants by selecting voluminous plants that encroach on each other as they grow. This organised imprecision creates a sense of mystery and invites reverie. Different heights of plants dotted with clumps create a gentle harmony of colour, using vertical inflorescence, preferably in conspicuous flowerbeds. These gardens have a certain hazy softness about them and toy with delicate nuances of colour. Oudolf also invites the gardener to understand and appreciate autumnal browns. Life is cyclical and it is ok to leave dead leaves and naked stalks to enhance the beauty of a garden… Especially when frost comes and gives them a shimmery, otherworldly glow.

These are some of the recommendations by Piet Oudolf. His landscaping footprint is constantly evolving and open; non conformist; and works towards creating nature that is not decorative as such but a rich and coherent ecosystem that is of aesthetic and practical service to its users.

Hummelo, the garden owned by Oudolf and his wife in the Arnhem region and which has evolved over several decades, is so famous it has become a tourist attraction. The designer’s great gardens include the legendary High Line gardens; the Remembrance Gardens (also in New York, and designed in memory of 9/11); Millennium Park in Chicago as well as numerous public and private parks in Europe.

- Jardin de Hummelo ( © the mocacelli press)

- Jardin de Pensthorpe Jardin de Hummelo ( © the mocacelli press)

- Jardin de Hummelo ( © the mocacelli press)

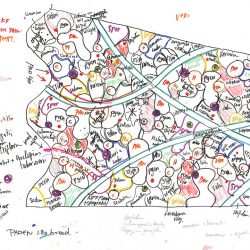

- Planche de conception (www.oudolf.com)

- Planche de conception (www.oudolf.com)

- High Line à New York (Livre Planting: a new perspective, photography © Piet Oudolf)

- Jardin de Hummelo ( © the mocacelli press)