Patterns in modern art

10.07.2016

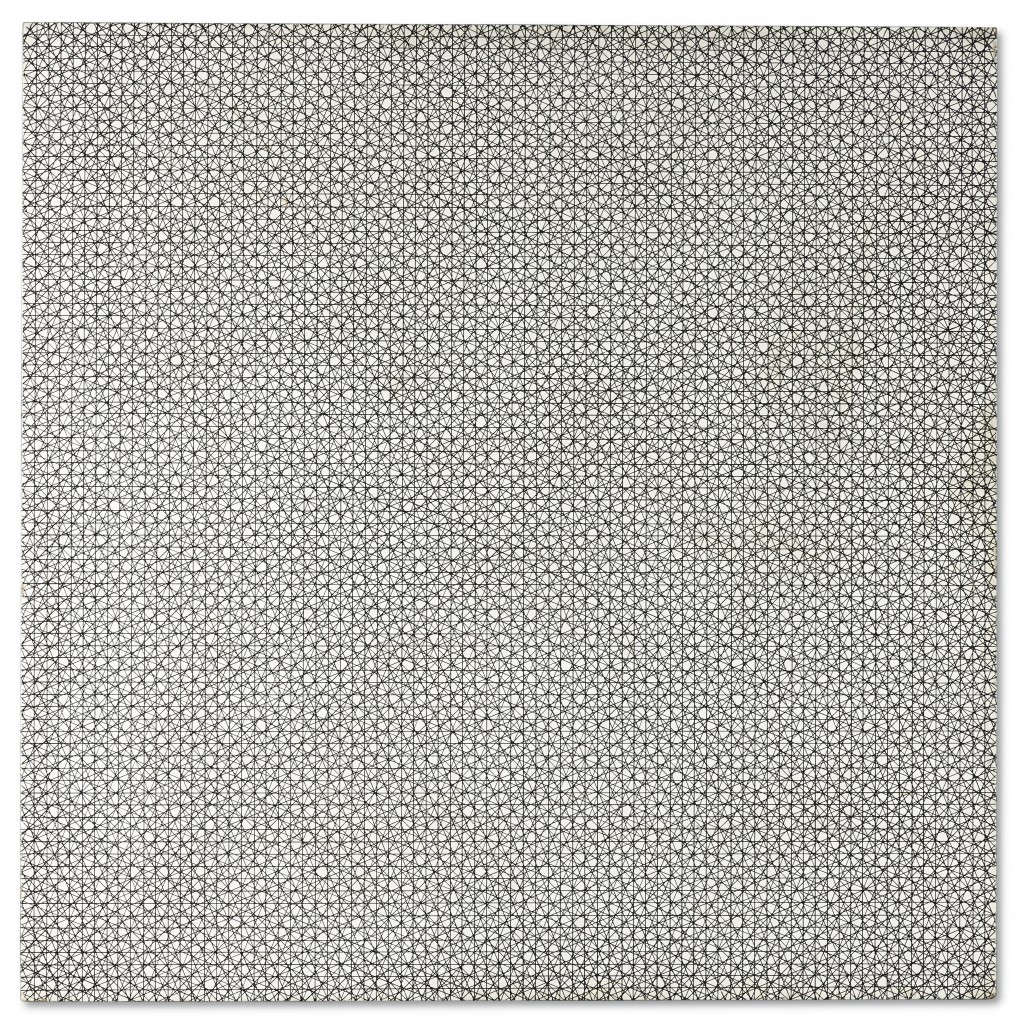

François Morellet (1926-2016), 4 doubles trames 0°-22°5-45°-67°5, 1958. Copyright : © Christie’s images, 2016

Patterns in modern art, by Paul Nyzam

Eschewing the romantic figure of the artist – a visionary and demiurge – many 20th century artists have worked on developing a demystified language, with the artist disappearing in favour of a system, framework or rule and in which the piece of work, willingly turned into a series of works, gains an autonomy that is beyond the will of its creator. It must be pointed out that artists had to take note of an era now marked by the mechanical reproduction of art, to use the now famous words uttered by Walter Benjamin. As photography and cinema flourished along with printing processes and the industrial production of manufactured goods, practices began to adapt to their new environment.

These reflections that filtered through the art movements of the past century have ended up spawning somewhat disparate pieces of work. This is certainly the case with Pop Art which, by involving the serial production of screen ink canvases, mirrored the mass consumerism that characterised Sixties America. When Warhol exhibited his thirty-two Campbell’s Soup Cans, all the same size and lined up side by side as if they were on a shelf in a supermarket, he imprints the image of the soup can on the retina of the viewer using saturation repetition methods similar to those used by the advertising world. At the other end of the spectrum it is the same story for minimalism that emerged at the same time as a response to abstract expressionism. The offshoots of forms reduced to their simplest expression – parallel lines and concentric squares for Frank Stella; metallic parallelepipeds for Donald Judd; wooden cubes as well as square copper and aluminium plates for Carl André; industrial neon for Dan Flavin – all respond to the prerequisite of « less is more » by removing any symbolic dimension from art and by confining the piece of work to its material reality only, whether that be lines, shape or colour, and nothing else.

In France it was François Morellet (until his death last May) who championed art exclusively proceeding from a system governed by principles that were determined in advance. Influenced by the motifs he stumbled upon in Alhambra in Granada in 1952 and which he said were « the most intelligent, precise, sophisticated and systematic art that had ever existed », using geometric and mathematical principles, he went on to define rules and constraints to guide the arrangement of shape and line (overlapping, juxtaposition, rotation, interferences, fragmentation) in the creation of his work. Using a ruler, measuring wheel and compasses – tools that are usually used by workmen rather than artists – for all his canvases, Morellet created all-over compositions that abolished the notion of foreground/background planes, horizon lines, depth effects, centres and margins. The autonomous motif therefore goes on and on to infinity and seems set to extend beyond the physical limits of the canvas.

In the Fifties and Sixties Morellet and his contemporaries subsequently showed the way for a generation of artists who are pursuing these explorations today by adding specific issues of the digital age into the mix. Artists like Wade Guyton (his inkjet prints playing on smudges and errors), Kelley Walker (replicating images from mass media to excess) and Mark Grotjahn (variations on centrifugal patterns) for example, all of whom are creating pieces of work with the question of pattern and repetition at their heart of the creative process.

Paul Nyzam is a Contemporary Art expert at Christie’s.