This ancient branch of Botany

08.15.2016

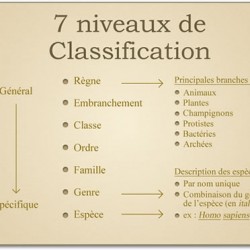

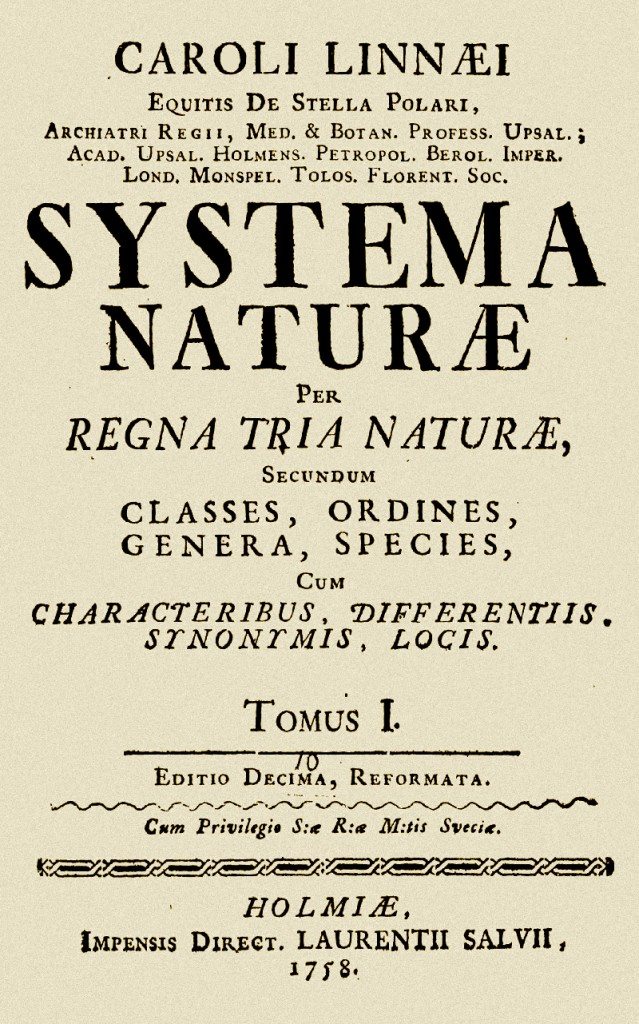

Carl von Linné - Systema Naturae En 1735, Carl von Linné (1707-1778) publie le premier essai de classification systématique des trois règnes minéral, végétal et animal. Son Systema naturæ divise les animaux en six groupes (Quadrupèdes, Oiseaux, Amphibiens, Poissons, Insectes et Vers), déterminés en fonction d’organes spécifiques : dents, becs, nageoires ou ailes. La dixième édition, de 1758, généralise le système de nomenclature binomiale (un double nom latin, générique et spécifique, pour chaque espèce).

Botany, the knowledge of plants, is as old as man. We have always nurtured and tended plants. We have produced books on botany during Antiquity, the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. But the subject only became a science – an autonomous field of knowledge – during the XVIIIth century.

The precursors of plants – cyanobacteria – date back 3.8 billion years; the first plants according to our definition of the latter appeared 475 million years ago followed by flowers around 135 million years ago. Proto-primates appeared 60 million years ago with Hominids arriving 7 million years ago, and from them Homo sapiens – all of us – popping up around 200 thousand years ago.

The word Homo sapiens is a Latin binomial that combines the genus Homo with an adjective denoting species of living organism, sapiens. This nomenclature (classification and naming methodology), established by Carl von Linne (1707-1778), is still being used today. He devised and implemented it whilst working as a botanist. The binominal nomenclature, followed by the author’s name and year, is used throughout the field of biology.

The founding fathers of modern botany are Joachim Jungius (1587-1657), John Ray (1627-1705) and Linne. They are like three trees that concealed the forest of great scholars who contributed to the foundation of the body of science called « Natural History » via their participation and debate. If all, or part, of the knowledge bank acquired was subsequently invalidated by the evolution of modern science (Darwinian revolution during the XIXth century; biology and life sciences etc), the method, systemisation, discrimination of fields to be considered and those to be discarded and the appropriate designations that formulate them went on to establish the foundations that speak volumes about the new age that emerged after the Renaissance and which is still going on today. Everything has been contradicted since then, but in a meaningful way, and using the same terms.

Back then, life did not exist. Nor did the living. There were only living beings. And the names that described them were perceived as being like the being itself: giving a plant or an animal a name was to describe everything about it, not just its reality but its medicinal and magical attributes; as well as how to plant it (or hunt it); the coats of arms that it might have appeared on; and the myths and legends surrounding it. The whole caboodle therefore, from fact to fiction.

The work undertaken by scholars of the time, perfected by Linne, was called taxonomy, the branch of science concerned with the classification of organisms by describing them and organising the research. This involved establishing a fixed and precise system of names to describe what could be seen: the visible being measurable as opposed to taste, smell and touch which were too vague. Invisible life forms obviously don’t appear on this phylogenic chart composed of criteria of identity and similarity. Linne defined 8000 different plants using his system of binomial nomenclature.

This new way of producing a record of the natural history of plants was based on the rationalisation of the relationship between what has been seen with the naked eye and a written description. This side of the birth of botanical sciences was studied by Michel Foucault (1926-1984) in The Order of Things, (in a chapter entitled Order). Debates were fast and fierce between scientists. As a so-called « creationist » naturalist, Linne thought living species had been created by God during Genesis and had changed little since then. Buffon and the French philosophers, including Diderot, advocated an epistemological approach to method that contrasted with the Linnean system and favoured the viewpoint that species changed over time. This was inassimilable to Charles Darwin’s evolution theory (1809-1882) as Darwin examined the organisation of living things. But all of these scientists established criteria for species and defined, classified and ordered them by name.

The botanical sciences that emerged after the Renaissance and that flourished during the classical period are done and dusted. This kind of science belongs to the History of Science. However, this history is a conduit for the discussion and formalisation of a scientific narrative, the literary matrix of which is botany.

- Carl von Linné – Species Plantarum

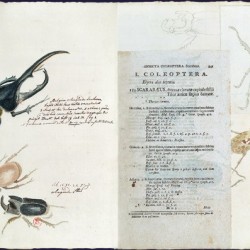

- Carl von Linné. Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ. Vienne, J. T. von Trattner, 1767-1770 – 2 vol. in-4o. BNF, Réserve des livres rares.

- La classification linnéenne

- Carl von Linné – édition anglaise du Systema Naturae, début du XIXe siècle