The vanished fresco

11.17.2017

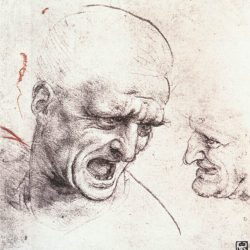

Léonard de Vinci (1452-1519) - Tête d'un guerrier ('le chef rouge ') - étude pour la bataille d'Anghiari, 1504-5, Musée des arts fins, Budapest

Is Giorgio Vasari’s wall painting the Battle of Marciano a brick palimpsest* of the Battle of Anghiari, a fresco sketched by Leonardo da Vinci? The Master considered it a key piece of work and it dazed those who saw it. However, apart from sketches, copies and historical records, this wall painting seems to have disappeared!

The Hall of the Grand Council (or Hall of the Five Hundred) had just been revamped at the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence. The time had come to allow Florentine families to participate in running the city by creating a collegiate body following the fracture between the extremely despotic Medici reign and Florence’s Republican roots. After the death of Savonarole, their successor to fanatic spiritual probity, it was important to perpetuate the existence of this Grand Council by expressing the dignity of the place via edifying works of art: hence calling upon the services of no less than Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo to conceive and paint wall frescos celebrating the city’s historical victories. Neither of the two artists, however, completed their commissions.

Leonardo da Vinci, a supernatural artist, was known for his slow execution and capriciousness, meaning that he had many works on the go at once but not all good. Also numerous letters written by Florentine patrons reveal their concern regarding completion of the cartoon prior to commencement of the wall painting, commenting on conditions, deadlines and remuneration in an odd blend of firm and conciliatory tones to twist the artist’s hand without being too derogatory in the process. He began work in autumn 1503 and continued until spring 1506. His subject matter was a battle won by the Florentines and Papist allies over mercenary Milanese troops near the town of Anghiari on the 29th June 1440 in Tuscany. The composition honed in on the central scene and the seizure of the enemy’s standard, one of the turning points of military engagement.

He finished the cartoon and it was exhibited alongside Michelangelo’s. Benvenuto Cellini, who sculpted the statue of Perseus, said the following about the Masters’ two cartoons: « As long as they remained intact, they would instruct the world. » As for the fresco, Leonardo’s experimental technique of using an undercoat so thick that after he applied the colours the paint began to drip was a failure. It seems that a despondent Leonardo da Vinci abandoned the work when he was opportunely summoned to Milan by Louis XII, the King of France.

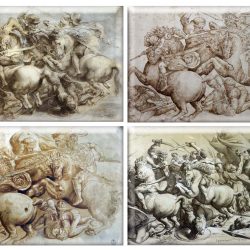

Only the central scene was done, but what a scene it was! When it was visible it was considered to be the apogee of Art. The work showed the grimacing, contorted faces of the Milanese who were so glued to their mounts that they looked more frightening than a raging monster, like a fiercely possessed hippogryph in fact, in contrast to the victorious Florentines, who were represented in all their chivalric nobility, remaining masters of humanity at the height of the conflict. The distribution of symbolic attributes, the fury of Mars against the prudence of Minerva, rounded off this iconographic presentation. The piece of work was spectacular.

« It would be impossible to express the level of Leonardo’s ingenuity when it came to the soldiers’ uniforms which he sketched in all their diversity, or the coats of arms, helmets and other ornaments, not to mention the incredible skill he demonstrated in the shape and features of the horses, which Leonardo, better than any other Master, captured with all their bravery, muscle detail and graceful beauty on show. » These comments were made by Giorgio Vasari, the very artist who covered the unfinished fresco of the Battle of Anghiari with Marciano’s painting in 1563. Could it be possible that Vasari would have had the audacity to paint over a great work by a Master he worshipped, or is it more likely that he would construct a brick wall in front of it and paint his own work on top of that – a tactic he had already used to safeguard the fresco of the Holy Trinity by Masaccio in the church of Santa Maria Novella in Florence?

This is Carlo Pedretti’s conclusion proposed in the Seventies. Amongst the various clues that support this hypothesis, the fact that copies of Leonardo da Vinci’s unfinished fresco made shortly before Vasari set to work demonstrate that it was still in good condition; and the presence of the inscription « Cerca, trova » (look and you will find) in Vasari’s fresco, which could be addressed to the sagacity of an inquiring mind in the future, might be a cryptic clue that the fresco might concealing another one underneath. The hint is fanciful and the subject of much debate; historians suggesting other explanations for the presence of these words.

Exploratory research initiatives were launched including ultrasound and radar techniques… and the space behind sounded hollow. In 2012, after years of work, Maurizio Seracini, an independent art expert who backed Pedretti’s hypothesis was allowed to drill six holes in Vasari’s fresco. The cavity was proved to exist and the information gathered using micro-cameras and endoscopic probes seem to corroborate the validity of the hypothesis without proving it as such.

It is ironic that Vasari, this « patron of the famous » (André Suarès), known for portraits of artists he had met and admired and to whom we owe the terms « Renaissance » and « Gothic », an ancestor of art history and also a minor artist in his own right, concealed the remains of major work of art from a key period in art history. Because « Leonardo da Vinci considered three pieces of work as crucial: the equestrian statue of François Sforza, the Last Supper and the Battle of Anghiari ». (André Malraux, 1951). The potential presence of a hidden masterpiece by one of the greatest and brightest geniuses mankind has ever known has been the driver for a flurry of investigations in an attempt to find it, leaving experts and art lovers hankering to know whether it will be necessary to destroy Vasari’s upper daub-layer to reveal the masterpiece below?

*: “a palimpsest is a manuscript page, either from a scroll or a book, from which the text has been scraped or washed off so that the page can be reused for another document”. (Wikipedia source)

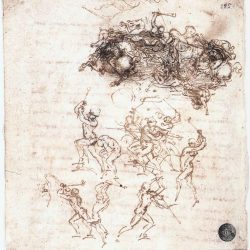

- Léonard de Vinci (1452-1519) – Etude pour la bataille d’Anghiari

- Léonard de Vinci (1452-1519) – Groupe de cavaliers dans “La bataille d’Anghiari”, 1503-4, Bibliothèque Royale, Windsor

- Léonard de Vinci (1452-1519) – Étude de combats à cheval et à pied, 1503-4, Dell’Accademia de Gallerie, Venise

- Léonard de Vinci (1452-1519) – Étude de combats à cheval et à pied, 1503-4, Dell’Accademia de Gallerie, Venise

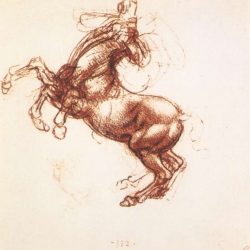

- Léonard de Vinci (1452-1519) – Étude des chevaux pour la bataille d’Anghiari, 1503-4, Bibliothèque Royale, Windsor

- Léonard de Vinci (1452-1519) – Élevage du cheval, 1503-4, Bibliothèque Royale, Windsor

- Léonard de Vinci (1452-1519) – Étude de batailles à cheval, 1503-4, Degli Uffizi, Florence de Galleria

- Léonard de Vinci (1452-1519) – Etude de tête pour la bataille d’Anghiari, 1504-5, Musée des arts fins, Budapest

- Léonard de Vinci (1452-1519)? – dessin préparatoire pour “La bataille d’Anghiari” (©the Trustees of the British Museum/Art Resource)

- Pierre-Paul Rubens (1508-1577) – copie de la scène de “La lutte pour l’étendard” de la bataille .d’Anghiari (Photo (C) RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Michel Urtado)

- Schéma de “La bataille d’Anghiari (copie d’un détail)” 1503-5, Degli Uffizi, Florence de Galleria

- Quatre copies “in situ” de la scène de la lutte pour l’étendard de la bataille d’Anghiari de de Vinci (probablement par P.P. Rubens, Ricellai, un anonyme et Commodo: sources internet non vérifiées)

- Salle des Cinq Cents, Palazzo Vecchio de Florence (photo©Yannick Bénaben)

- Sondes dirigées par Maurizio Seracini en 2012, au travers de la fresque peinte par Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574)

- Sondes dirigées par Maurizio Seracini en 2012, au travers de la fresque peinte par Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574)

- Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574) – Bataille de Marciano (détail)