The sensible seal

02.20.2017

Portrait de René Descartes (1596-1650) par Jan Baptist Weenix (162-1659/61), Utrecht Centraal Museum.

The wax argument by Descartes is, of course, a sensational philosophical thought process that is now very well known in the history of philosophy. All unfounded certainties ‘melt’ in it but from this melting process comes the spiritual honey.

In The Meditations on First Philosophy published in 1641, René Descartes (1596-1650) re-examines old opinions, beliefs and feelings using a philosophical approach aimed at basing all knowledge on firm foundations. In his second meditation he uses the example of a piece of wax subjected to heat to show how unreliable any assurances acquired via the senses can be.

« Let us take, for example, this piece of wax: it has been taken quite freshly from the hive: and it has not yet lost the sweetness of the honey which it contains, it still retains somewhat of the odour of the flowers from which it has been culled; its colour, its figure, its size are apparent; it is hard, cold, easily handled, and if you strike it with the finger, it will emit a sound […] But notice that while I speak and approach the fire, what remained of the taste is exhaled, the smell evaporates, the colour alters, the figure is destroyed, the size increases, it becomes liquid, it heats, scarcely can one handle it, and when one strikes it, no sound is emitted.. » Now this is the very same wax. And what happens to the wax happens to everything: flesh, soil, plants, stones, everything erodes, corrupts, decomposes and recomposes in different time scales. Nothing that is perceived by the senses is reliable because the properties being perceived are unstable, labile and temporary in nature. What the senses perceive comes from the imagination, which presents inconstant and uncertain properties.

But to overcome this perception informing imagination and constituting common sense, there is the mind. The latter, informed of the inconstancy of perceptible things, is acquainted with other qualities. It understands that the state of the wax is « something extended, flexible and moveable. » And only the understanding of the mind can deduce that. Intellect alone penetrates reality.

The example of wax (the model in short, in that it is modelled on the conditions that alter it) is instructive thanks to its plasticity. The fact that it is something extended means that it holds universal value for all matter, and thereby invalidates the authenticity of sensible forms. They are just illusions. Behind this apparently simple example of scholarly inference, the philosopher is of course addressing Aristotle, who had also tackled the example of the malleability of wax to conclude the opposite of inverted resemblance but nevertheless a true reality for the one who feels and that which is felt, just like an object buried in wax leaves a trace in the hollow. There are even more burning implications with the all-powerful scholastic thought of the time, and the conception of God.

For now the pool of wax makes a powerful statement. What appears to us to be the face of things persists without knowledge or the ability to see things clearly in a sensible way, putting senses on a back burner.

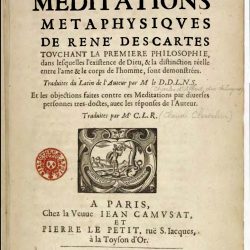

- Les Méditations Métaphysiques de René Descartes