The logic of organised sensations of Cezanne

10.27.2017

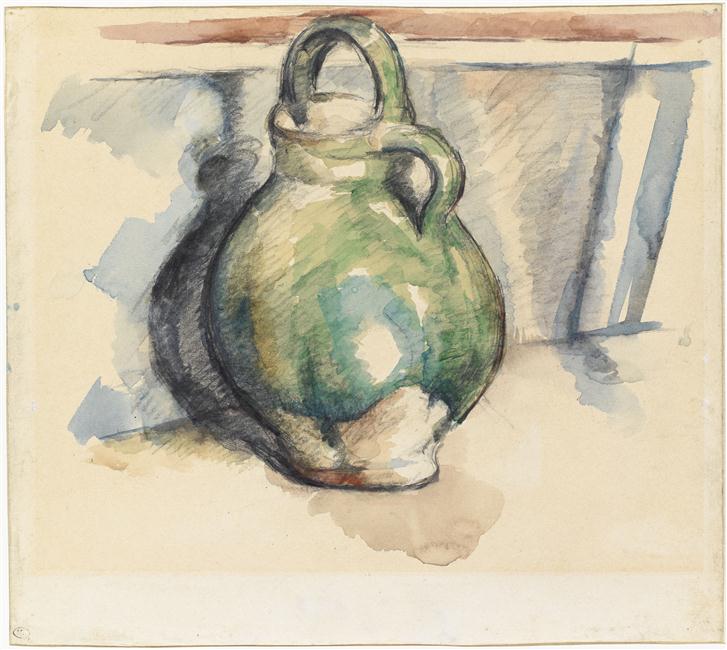

Paul Cézanne (1839 - 1906) Le cruchon vert (Photo© RMN-Grand Palais (musée d'Orsay) / Tony Querrec), Musée d'Orsay, conservé au Musée du Louvre, Paris.

Cezanne: the logic of organised sensations according to Lawrence Gowing, by Julia Kerninon

Art historian Lawrence Gowing, an expert on Cezanne’s work, offers a new perspective of the master’s works in this essay. Perhaps because he is a painter himself and that’s why Gowing focuses primarily on technique and materials. He takes the canvas in, looks at it as it is, rather than wondering what it demonstrates or proves and how to intrepret it.

Gowing relies on highly fruitful extracts from Cezanne’s correspondance and on the writings of the famous Emile Bernard. He documents his insights in a thorough manner, inviting the reader to focus his or her attention not on the geology of Mt Sainte-Victoire, but on the colours, the lines, the connections, as Cezanne called them. « There is no line, there is no modelling, there are only contrasts », he declared, whilst pursuing his artistic training with quasi-religious zeal. When he saw one by one, the canvases in an exhibition called Cezanne, The Late Work, in New York at the Museum of Modern Art which ran from October 1977 to January 1978, Gowing decided to retrace the artist’s evolution, his various attempts to « read nature » via the « colouring sensations » that he evoked towards the end of his life.

The exhibition catalogue that accompanies this essay provides an exciting illustration of Gowing’s ideas: a watercolour called Le Cruchon vert (The Green Pitcher) appears to be a key work in the development of Cezanne’s thought processes when Gowing points out its uniqueness. We also discover Cezanne’s unusual view of watercolours, which he regarded as an art in its own right not simply sketches for a painting, and this meant a different approach and technique to the subject matter.

Remarkable acumen aside, this short essay respects Cezanne’s ambition and commitment: Gowing appraises the paintings within this framework. He celebrates Cezanne’s meticulous approach, which is also the source of his greatness, and concludes by touching on the despair of the artist in his later years when it dawned on him that he might die before achieving perfection in his art: « The real achievement of a great artist is his life. »

Julia Kerninon is Doctor of English literature and writer.