The hippie and the liberalism

03.05.2018The hippie, with flowing locks, embroidered floral jacket, contentious cigarette and words of brotherly love, is the figurehead of Sixties revolution. Following the rebellion of James Dean, Elvis and the beatniks, the hippie rose up to herald the new world like a mystical mutineer.

History can’t be cut up into neat little slices; the decades remain a reflection of an attitude of mind. But some eras cause reactions that end up changing the cultural environment, our way of life, our relationship with pleasure, thought and even faith. One such era was the «Sixties », especially in the USA and in Europe. The initial cause of this was demographic. The great post-war baby boom had reached adolescence. These years were marked by an upsurge of nubile sap that washed over the temperance of bourgeois morals that were more of a repressive yoke round people’s necks than something to be revered. For example, until the end of the decade in France, a married woman was legally under the authority of her husband and couldn’t apply for a job without his written authorisation. And children had no say whatsoever. Such subjections were obsolete in a consumer society with materialistic, consumerist and egalitarian ideals that produced goods not just to satisfy need but increasingly to satisfy cravings generated by advertising. Had the sin of greed been raised as a moral injunction for economic salvation? In short, the morality of yesteryear had nothing to do with business. And business, that’s to say, commerce, induced a benefit that was more than pecuniary: that of profiting from life. With this in mind, the new upstarts would find their voices.

The violent protest of the new generation, often students, turned into genuine moral discord for certain groups of people such as the hippies who simply wanted to turn their backs on society of the time. The joy that they preached had an orgiastic and cosmic dimension. Narcotics played a part. Sedition is radical; they wanted to break away from the modern way of life, the model of which was becoming internationalised by gradually unifying its behaviours. Such an insurrection needed to justify itself; even more profoundly than the intellectual and artistic sources that modelled its discourse, it intended to proceed from a spiritual origin that allied the self with the cosmos and in contrast to the narrow and secular Christianity of the parents there was now a whole mystical arsenal to sift though that included Buddhism, Hinduism, ancient myths and Amerindian shamanic rites etc. Pleasure became sacred. Hedonism « ic et nunc » is regarded as a magical initiation.

The road from individual to self is long. However, the limiting experience of an LSD trip desired by the wayward teen and the mystical ecstasy experienced by the devout as a result of faith and fasting were readily believed to be of the same nature. And the great preachers like Alan Watts, an eminent prophet/philosopher (former Episcopal priest converted to Zen Buddhism, which he taught for a number of years, and an academic, theologian, writer and sycophant of « acid » in The Joyous Cosmology published in 1962) and Timothy Leary, (psychology professor at Harvard and apostle of cognitive and spiritual enrichment by using LSD), wrote about it and justified it. The latter worked to establish a psychedelic religion with his liturgy… If Aldous Huxley’s essay The Doors of Perception, dealing with his psychedelic experiences and their patent interests was a reference work (rarely read, always cited), his profound and spiritually erudite work, Philosophia perennis, was not. However his final novel, îles, published in 1962, was a roaring success among the rebellious youth and played a key role in their minds, emphasising the utopia of a harmonious and ecologically-minded society that resorted to mescaline-assisted meditation.

Because hippies, along with other movements of cultural insurgency at that time, and everyone of this generation who took part in this upheaval of cultural mores and promoted their right to enjoyment, were all sincere in their intentions. And they considered these things to be necessary. They believed in it, the artists among them released plenty of inspired (and leftfield) albums to that effect as well as other forms of art that were considered legitimate. Their spiritual aspirations were visceral in nature. The list would be long. The individual was free, did not have to account to the ancients, and the sovereign body was a place for travel, that’s what was consecrated. The mystical aspirations of people that made this era so colourful was undeniable, their spiritual experiences may have been genuine but they nevertheless took their pick from the global spiritual corpus to reinforce their mindsets, setting aside the bits that failed to please and concealed their inherent constraints.

The originality of these Dionysian outbursts of counter-cultures which spread like an epidemic among a fragile fringe of young people, especially during the psychedelic period in the late Sixties, was also full of enlightening contradictions. On the one hand because they were the subsequent manifestation of a system of production that the older generation had put in place for them without anticipating any moral (value related) significance. The hippie is the Frankenstein of the bourgeois. On the other hand, because their non-cooperation when it came to mystical impulses made the collective imagination more real and this never ceased to be taken up by fashionable culture, advertising boasting about pubescent rebellion and that became trivialised by everyday spiritual syncretism, or via words that were poorly understood – karma and ego – the ideals of benevolent detachment and eco-responsibility were happy bedfellows with the accumulation of goods and the intemperance of entertainment, with a little bit of charity thrown in for good measure. A tragic irony, this Sixties counter-culture was an effective cultural cast for the consumerism and behaviours that have successfully followed in their wake since then.

To the parents who worked hard for a consumer-free society and who were horrified by a new generation that interpreted free consumption on its own terms, just like those who still deplored the moral consequences of the upheaval in values that took place in the Sixties, these words by Bossuet, misrepresented over the ages, are a rejoinder that echo through the centuries: « God laughs at men who complain of the consequences whilst cherishing its causes. »

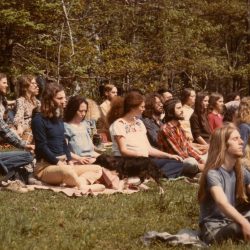

- Méditation dominicale (Sunday meditators from hippycommune.wordpress.com)

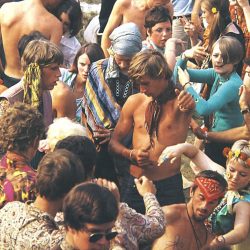

- “Summer of love”, San Francisco, Golden Gate Park (Alph Crane LIFE Picture ©Collection Getty Images)