The hand of the soul

08.04.2017The line of a drawing is like a thread emerging from obscure depths, a psychic chaos haunted by monsters that lands on the whiteness of a sheet of paper. Alfred Kubin illustrated fears. This noble artist on a quest for wisdom also reflected on the nature of his art: drawing.

The visions of Kubin (1877-1959), an Austrian draughtsman, illustrator, printmaker and writer are often more well known than his name and still pop up here and there in themed exhibitions, mainly as illustrations of great novels that made him famous during his life. His name is also linked to an art movement called Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) along with pictorial artists and friends Vassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee.

Drawing is an art of the sign that reveals the unknown. Its simplicity is hard to beat. A drawing « can make everything clear with practically nothing. », but it requires a hand that is a faithful seismograph of inner turmoil. This is what turns a drawing into « the mark of the soul ». This mark expresses a vision, be it psychic or real, and transforms a confused and teeming reality in just a few lines, the thickness of which convey expressive intent and significant fervour whilst dealing with the void that surrounds them. This is what turns drawing into symbolic art in Kubin’s eyes and despite practical appearances and proximities this makes it to closer to poetry and music than painting.

His artistic vision was often an expression of his primitive childhood terrors that continued to mushroom in the depths of his consciousness. His first task was to let them rise up from these intimate abysses and welcome them into his imaginary field of vision. But unlike psychoanalytic work searching for intellection via symbolic analysis and correspondences, his work tried to preserve their integrity in order to see them and show them as they appeared in « the twilight of the soul. »

Only this exercise allowed this. Kubin distinguishes two factors in creating a drawing: rhythm and construction. Rhythm is precisely that unknown influx that animates the hand. The drawing gives the eye rhythm, a kind of pictorial vitality, with roots deep in the artist’s most private impulses: this rhythm is neither learnt nor developed; it’s the very uniqueness of the creator that permits its transcription in lines. Whereas the construction stems from the artist’s reflections, allowing him to organise his visions in meaningful abstractions with meagre means such as lines, dots, tasks and emptiness. Rhythm and construction are blurred to the viewer but the artist gains knowledge by discriminating between these two processes in order to perfect the personality of his expression.

Alfred Kubin, a man of culture, read a lot and looked at many drawings to progress in his understanding of the threads of his art. This art of the exact line is like a javelin being pulled back from the soul and it made him appreciate classical Chinese art as being the highest manifestation of drawing. In the West, Rembrandt was the Master whom he consulted like a holy book. He knew the written representations of all the great engravers and their strengths and limitations from the Middle Ages through to the hallucinatory drawings of Van Gogh. But he found their lessons intimidating. Kubin praised his era for having opened up drawing to minor and less skilled artists as well as opening his eyes to the drawings of children, the alienated, the unknown and mediums, all of whom dishevelled the infinite threads of drawing.

Alfred Kubin wanted to find his way in a world that felt like maze, « and it’s by drawing that I have to do it. » Despite being a philosopher, he fled from ideas in favour of this quest to release his muffled inner depths, this mute Self from which shadows and abominable figures emerged that he associated with the primitive chaos of the world.

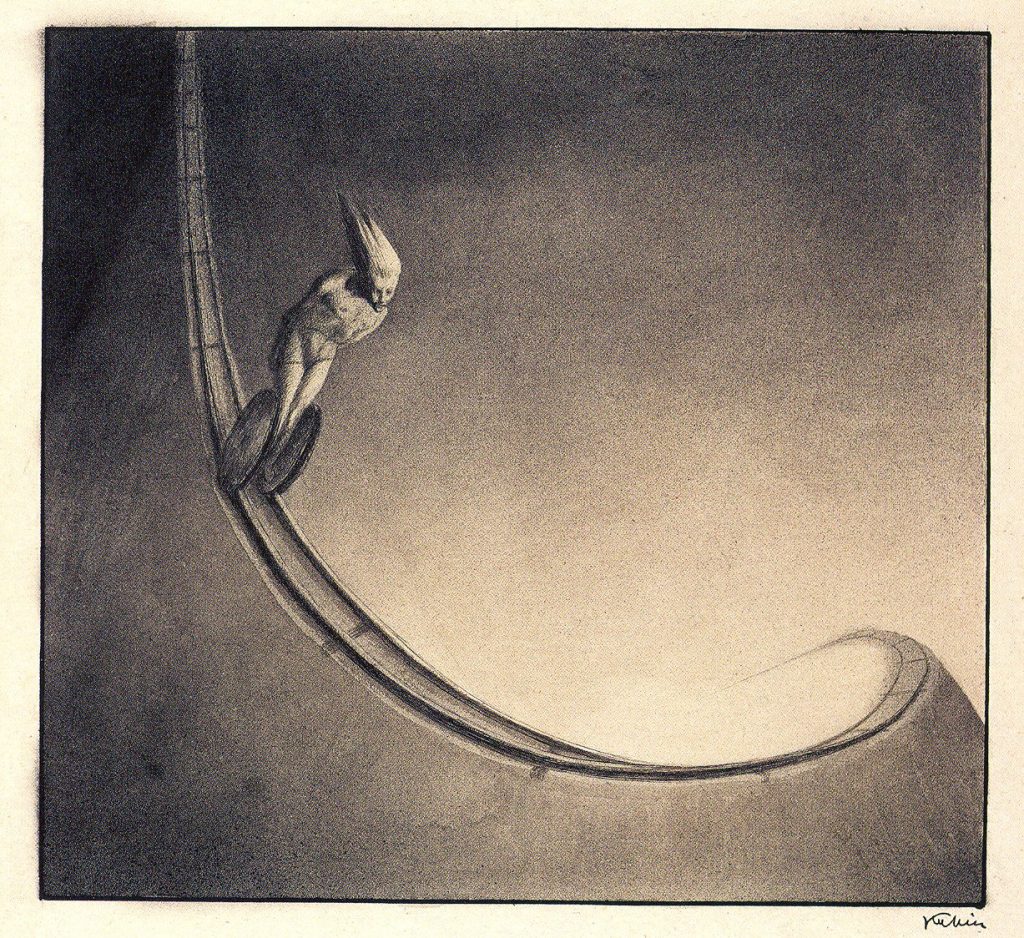

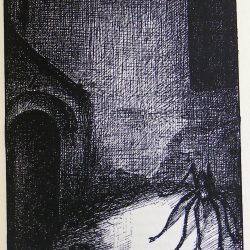

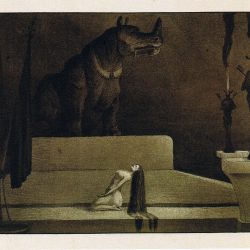

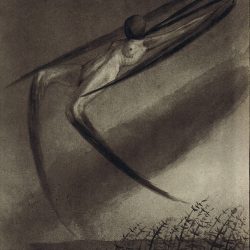

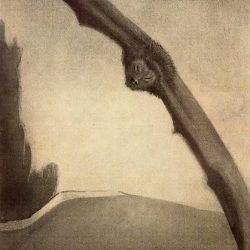

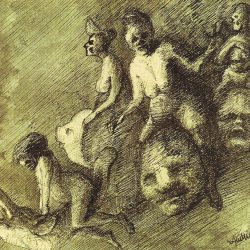

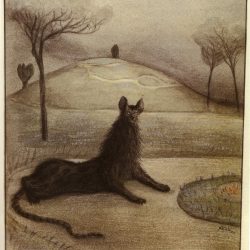

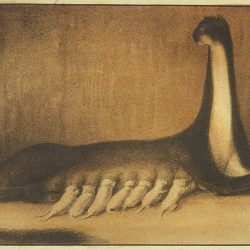

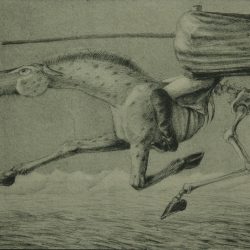

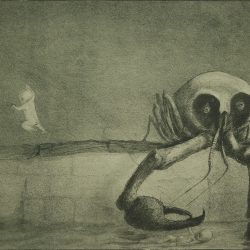

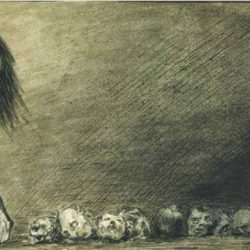

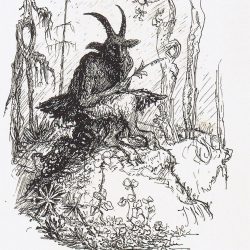

- Alfred Leopold Isidor Kubin (1877-1959), illustration.

- Alfred Leopold Isidor Kubin (1877-1959), illustration.

- Alfred Leopold Isidor Kubin (1877-1959), illustration.

- Alfred Leopold Isidor Kubin (1877-1959), illustration. “Chaque nuit, un rêve nous rend visite”.

- Alfred Leopold Isidor Kubin (1877-1959), illustration.

- Alfred Leopold Isidor Kubin (1877-1959), illustration.

- Alfred Leopold Isidor Kubin (1877-1959), illustration.

- Alfred Leopold Isidor Kubin (1877-1959), illustration.

- Alfred Leopold Isidor Kubin (1877-1959), illustration.

- Alfred Leopold Isidor Kubin (1877-1959), illustration.

- Alfred Leopold Isidor Kubin (1877-1959), illustration. “L’œuf”.

- Alfred Leopold Isidor Kubin (1877-1959), illustration. “L’heure de la naissance”.

- Alfred Leopold Isidor Kubin (1877-1959), illustration. “La destinée humaine”.

- Alfred Leopold Isidor Kubin (1877-1959), illustration. “Terre, notre mère à tous”.

- Alfred Leopold Isidor Kubin (1877-1959), illustration.

- Alfred Leopold Isidor Kubin (1877-1959), illustration.