The chance or Mr. Proust

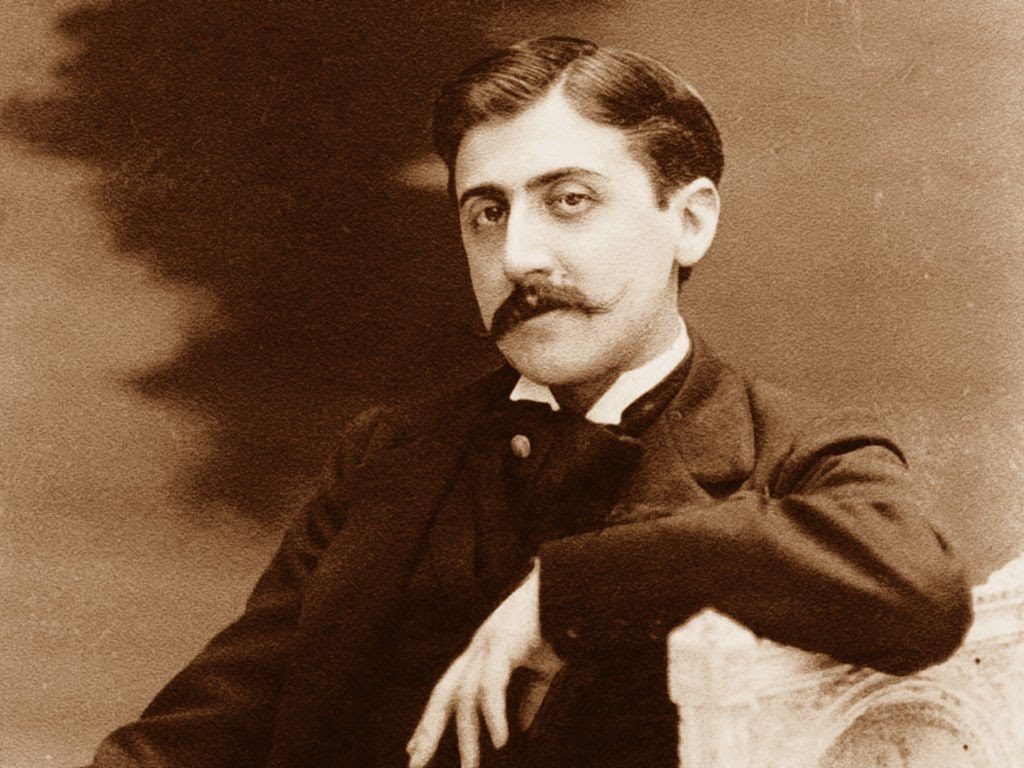

10.12.2018In a draft foreword for his posthumously published book Contre Sainte-Beuve, Marcel Proust testifies that chance alone has revealed to the writer the substance of his art: his emotive memory, against intelligence which impairs and counterfeits it.

One day, when the writer returned home numb with cold, his old cook brought him some tea: “And as chance would have, she brought me some slices of dry toast. I dipped the toast in the cup of tea and, as soon as I put it in my mouth, and felt its softened texture, all flavoured with tea, against my palate, something came over me–the smell of geraniums and orange-blossoms, a sensation of extraordinary radiance and happiness; I sat quite still, afraid that the slightest movement might cut short this incomprehensible process which was taking place in me, and concentrated on the bit of sopped toast which seemed responsible for all these marvels; then suddenly the shaken partitions in my memory gave way, and into my conscious mind there rushed the summers I had spent in the aforesaid house in the country, with their early mornings, and succession, the ceaseless onset, of happy hours in their train. And then I remembered: all the days when I had dressed, I descended into the room of my grandfather who just awakened and took his tea. He dipped a crispbread and gave it to me to eat. And when the summer had passed, the sensation of this crispbread softened in the tea provided a refuge where the dead hours – dead to the intellect – went to nestle and where I would, no doubt, never have recovered them , if that winter evening, returned frozen by the snow, my cook had not proposed that potion which was linked to that resurrection by virtue of a magic pact which I did not know.”

This artist, one of the greatest to dedicate his entire present to reviving the past through words, gave this example to assert his magical theory: “as soon as each hour of one’s life has died, it embodies itself in some material object and hides there. There it remains captive, captive forever, unless we should happen upon the object.” Only chance brings such objects to our attention and releases the soul of that hour, the memory of its sensation, which was entrenched in it and the awakening of which subsequently brings back all the hours that were related to it.

Marcel Proust compares such hours to ghosts of the past, offering him “helpless arms, like the shadows which Aeneas encountered in the Underworld.” Sometimes, transfixed before some object which intimates him to release the memory which has taken refuge in it, the memories are denied him and the past remains a nameless grave.

The writer’s intelligence cannot revive these hours that are a thing of the past, and these never take refuge within it. Their asylum is outside the reflective consciousness. “Alongside this past, the intimate essence of ourselves, those truths of intelligence seem to be almost unreal.” The writer in no way denies the intelligence necessary for his work, but he recognises that it is subordinated to the “feelings of joy” that it connects and dramatizes.

The author of In Search of Lost Time, who waits for chance to show him, once again, a life that was dead to him, is not however the pedantic clerk of trustworthy recollection. Sensation, emotion and feeling matter. They are the truth of the past. The facts are there for them. The novelist retains his poetic licence, starting by transforming slices of toast, which themselves are reminiscent of crispbreads, into a madeleine dipped into a cup of herbal tea…