Symphony for one man alone

01.07.2016

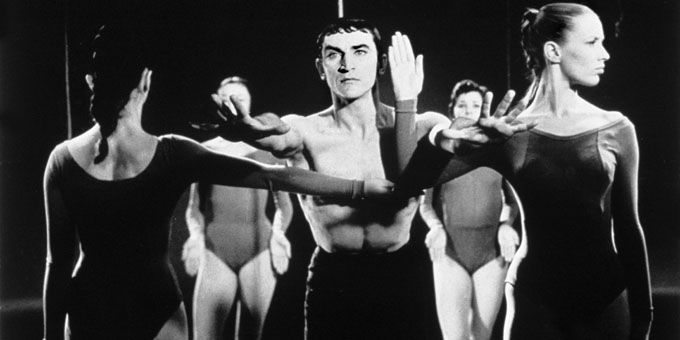

En 1966, Maurice Béjart a chorégraphié la Symphonie pour un homme seul au Palais des Papes au Festival d'Avignon.

«Symphony for one man alone» or listening reinvented, by Karine Le Bail

On the 18th March 1950, in the lovely auditorium at the Ecole Normale de Musique in Cardinet Street in Paris, Pierre Schaeffer is catching his breath: the « first avowed concert of real (« concrete ») music is about to start. The programme features the Symphonie pour un homme seul (Symphony for one man only) composed by the engineer-musician for four hands with Pierre Henry, at that time a young man fresh out of the Conservatoire de Musique in Paris. Schaeffer had already spent a number of years experimenting with sound in a small studio belonging to the French Radio Broadcasting institution nestled in the heart of Saint-Germain-des-Pres. In 1948, the discovery of sounds immobilised within the confined grooves of a flexible disc marked a radical turnaround: these were « pure » sounds within themselves. When repeated you forgot that they were the sounds of a train, and when cut you could no longer tell that the original sound had for example been a bell, it suddenly sounded like an oboe… This new acoustic sound, « neither music or noise », Schaeffer dubbed « Concrete Music », meaning it was a new way of approaching music by manipulating recorded sound in a studio.

In the first row of the orchestra at the concert hall, the « inventor » of concrete music slips behind a mixing desk with rotating potentiometers. Schaeffer had finally realised his dream of invisible listening, accompanied on stage by a couple of turntables sandwiched between two speakers located « quite audaciously in the magic circle where people are used to seeing the vibration of strings, the whistling of bows, the beating of reeds under the inspired command of the conductor’s baton ». Just like the innovators of the past – and futurists with their « concerts of direct sound » –, he anticipates a magnificent ruckus, « a real battle, one of those controversies that consolidates discoveries ». But none of that came about.

The Symphonie pour un homme seul, with its « terrible stamping of footsteps on the stairs, the pounding on the door, a direct conduit to the terrors of the Gestapo », is in keeping with memories of the war and the feelings of isolation felt by a man stuck in the thick of it all. With its “prepared piano” (Cage) and beautifully editing by Pierre Henry », the « hoarse breaths », the « onomatopoeia showcasing the exhausting battle between couples and armies», it is a good depiction as Schaeffer said of a man « firing on all cylinders and laughing at his own misfortune ». The Symphonie pour un homme seul would end up being played around the world several times thanks to Maurice Bejart’s ballet. The concrete music composed by Schaeffer and Henry inspired the choreographer to dream up new steps and movements, communicating the fear of a man facing a crowd in a language that was superbly energetic and expressionist in nature. Other famous ballets followed as a result of the collaboration between Bejart and Pierre Henry, such as The Green Queen, High Voltage and of course Mass for the present time and the famous Psyche Rock, a piece of work continually reinvested in by creatives from all the performing arts including choreographer Herve Robbe in January 2016 at the Philharmonic in Paris.

(Quotes by Pierre Schaeffer have been sourced from A la recherche d’une musique concrete (In search of real music) and Antennes de Jericho)

Karine Le Bail is an historian (CNRS / EHESS) and the producer of the A pleine voix radio programme (France Musique).