Slowness

09.02.2016Can slowness be measured? For some it should be considered in relation to an external sense of pace; for others in relation to a period of time that they long to experience. It is invariably defined as a lack of speed. But if said slowness is considered necessary, what kind of correlation does it have with memory and words?

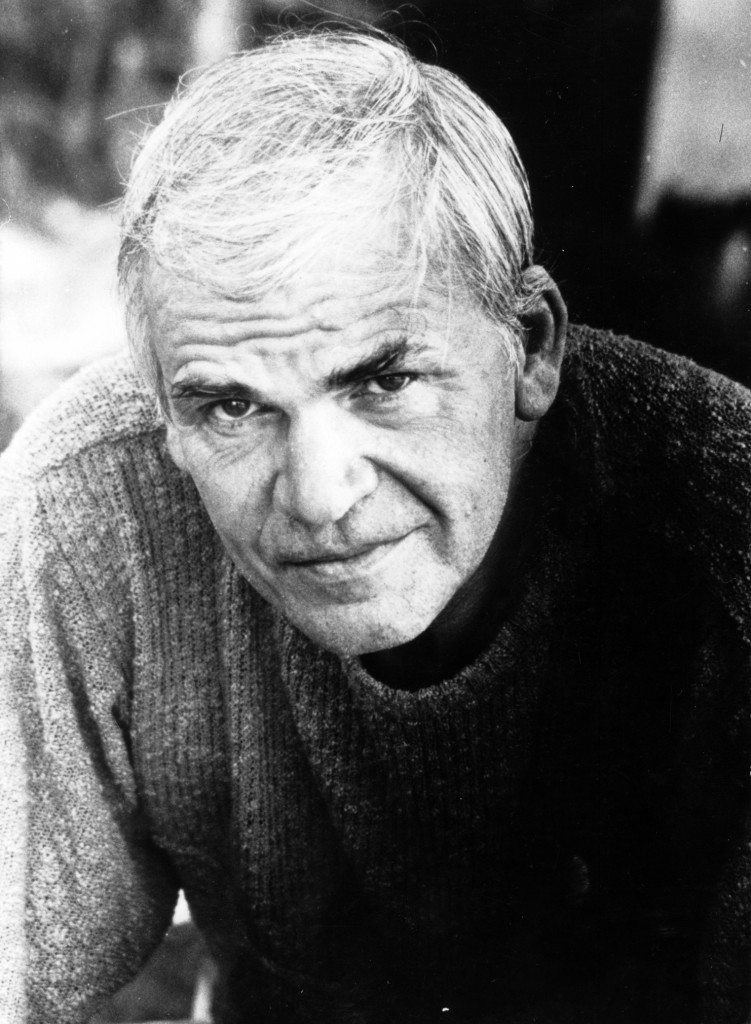

Milan Kundera is a writer born in Czechoslovakia in 1929 who became a naturalised French citizen in 1981. He called his first novella in French La Lenteur (Slowness). This short story links two tales of seduction separated by time: one a farce ridiculing a particular modern western society comprised of intellectuals and scholars obsessed with their image and the notches on their bedposts; the other the tale of Vivant Denon (1747-1825), a libertine who chose to remain anonymous, in Point de lendemain.

No surprise that the era of horse-drawn carriages and candles went at a more unhurried pace than a time of cars and electricity. Slowness is relative when compared to mechanics. You only have to take into account Denon’s understated, concise and direct style to appreciate its velocity: the characters are of their time (tail end of the XVIIIth century when a vivacity of spirit and a sense of appropriateness were crucial advantages when pursuing both political ambitions and amorous liaisons. Subtlety is par for the course. On the other hand, characters depicted by Kundera, who find themselves meeting up in the same castle where Denon’s tale took place two hundred years before, are oafish, crude and have no flair. So how does their fast pace become so burdensome, and what is this slowness exhibited by their ultra dynamic predecessors?

Things are supposed to move forwards: the art of the moment makes all the difference. For XVIIIth century libertines, this art is dictated by the verb: they describe what they are doing and are never outdone by repartee that tackles the outcome of the matter in hand: they conceal or disguise the reality of their intentions to win the most prolonged sensual delights available. Furtive glances and dialogue set the scene. They are patient and know how to manipulate time to their advantage. The memorable then becomes their prize. And memory randomly unfurls what has been experienced via the interstices of language. The contemporaries described by Kundera are restless. Their art of the moment is dictated by images. Staging is public. A limitless narcissism drives each individual to express his or her truth, but the brouhaha of each person at the same time prevents anyone from hearing what is being said. They are followed by the gaze of the other person. They are out of tune and dissipated. Of course they are attracted to modern technology. The moment has gone. Their speed only ends up chucking them on a course to oblivion. And memory is abandoned because they would feel ashamed of how they are reflected.

Milan Kundera lets the reader be the master of decisions. But he is definitely against cameras and a public setting where everyone is rushing about in all directions. The private trade of dialogue leads to shared time. This kind of time flourishes in the moment as much as it does in our memory banks. This kind of slowness is time spent knowing how to live, starting with being within the time rather then always and only in time.