A rough guide of Print-Making

11.19.2015There exist many varied techniques grouped together under the term ‘print’, each of which has its own fascinating history and artists who have excelled at its use. Print-making, that is the ability to create an image and then to reproduce it exactly again and again, has been around for many centuries. Arguably, our neolithic ancestors‘ handprint on a cave wall could be said to be the earliest form of stenciling, or print-making.

Pick up a dictionary of print-making, and you can quickly feel overwhelmed by the sheer number of techniques discussed, and their complexity. The starting point for any print is the surface it is produced on (the matrix). Two essential types of surface exist: a ‘raised’ surface or a ‘flat’ surface’.

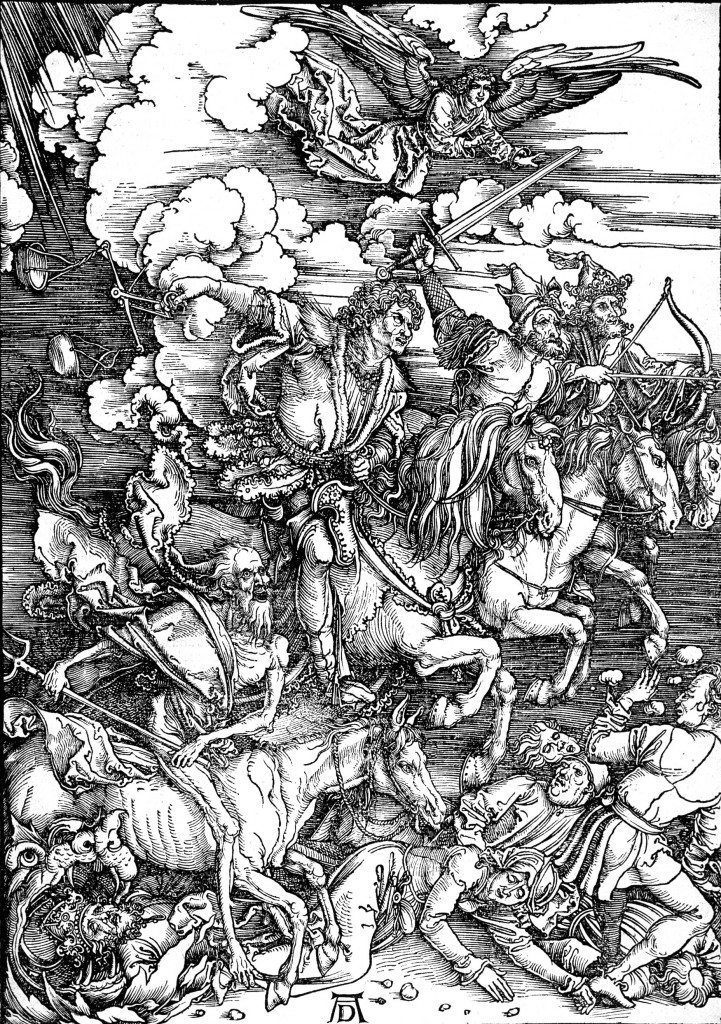

In a raised surface print, the image is created by cutting or scratching it into the matrix. Examples include the woodblock, linoblock, engraving, or etching and aquatint. Woodblock prints, where a design is cut into a block of hard wood are perhaps the oldest form of artistic printmaking dating back to the 9th century in Asia and to the 14th century in Europe, including Albrecht Durer’s outstanding Apocalypse series of 1498. Engraving, another ‘raised surface’ technique involves cutting or scratching a design by hand into a metal plate. This was widely used in both the northern and southern renaissance. Lastly in this category, etching (and its related technique of aquatint) also uses a metal plate as the matrix, but here the artist uses acid to ‘eat’ the design into the plate rather than a hand-held tool. Rembrandt is considered a master of this technique, and more recently Picasso produced over 500 etched images. Jasper Johns, Barnett Newman, William Kentridge and Peter Doig all made etching a central part of their art.

The second group of print-making techniques are those where the image rests on a flat surface. Lithography, screenprinting and modern inkjet and photographic printing techniques all involve using inks or pigments which are transferred from or through a flat surface onto the paper. Lithography is a complicated process, involving many more steps to transfer the final image than most other techniques. At the height of its popularity in the 19th century lithography studios multiplied throughout Europe where artist such as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Edvard Munch would seek the assistance of the highly skilled artisan lithographers. Screenprinting is a much more recent technique, developed in the 20th century and most notably adopted by the pop artists, especially Robert Rauschenberg and Andy Warhol, for whom its industrial origins subscribed to their concept of art for all.

Print-making in the 21st century continues to thrive with the variety of techniques growing as technology introduces further development. The original compelling reasons for artists to turn to print-making remain: to broaden the possibilities of what they can produce, and that the techniques themselves can often add unexpected and welcome developments which take the artist in new directions.

Tudor Davies, Head of Impressionist & Modern Art Department, Christie’s Paris (formerly Head of Prints at Christie’s New York)