Perfumed wigs

02.16.2018Perfumed wigs, by Annick Le Guérer

The XVIIth century was marked by a major fashion evolution in the world of hair. During the reign of King Louis XIIIth the popularity of wigs skyrocketed. They weren’t just a way of concealing bald spots or thinning hair, now they had become an essential part of the dressing process both for people in the city and at court. Wig powdering was the must-do, finishing touch.

Neither sex could claim to be elegant if their wigs were not powdered and perfumed. Not powdering your wig was a sign of mourning and even nuns were sometimes powdered like miller girls.

Scented powder was all the rage. It varied considerably in quality and price. Good quality powder was fine and stayed put on the wig because it is particularly objectionable to witness powder scattering onto clothing with the slightest movement of the head.

Glove-perfumers who now dominated the perfume market were right on point and paid particular attention to this fashion trend. On the 4th July 1689 they obtained the right to call themselves powder makers. This was a victory over starch makers, barbers and haberdashers who also harboured ambitions in this regard.

It is significant that in Simon Barbe’s book Le Parfumeur Royal (The Royal Perfumer) there is an important chapter devoted to the topic called ‘Treatise on hair powders.’

The foundation of these powders was the whitest and driest starch possible, to which the carbonised and ground bones of cuttlefish, bullocks or sheep were added.

Several shades were available, red, fair and grey. The last, and most popular of these, added a touch of silver to the wig, hence the expression powdered frosting.

Powder was scented in many ways. Flowers most used included jasmine and rose petals, hyacinths, daffodils and orange blossom. Ambrette powders followed, scented by frangipane and iris blossom. These floral notes were often given extra punch with musk, civet and amber. Powder for seafaring wigs combined cuttlebones, incense, myrrh, sandalwood, benzoin, storax and cloves. Polvil powder included nutmeg, calamus, cloves, cinnamon and a dominant note of oak moss. One of the best known powders was Maréchale powder named in honour of the Maréchale d’Aumont who is thought to have invented it. It was composed of many finely ground ingredients including iris blossom from Florence, rose petals, coriander, nutmeg and cloves.

During the XVIIIth century, hair fashion reached new peaks and powder served to keep towering constructions in place. They tended to produce abominable dirt on the forehead, neck and shoulders. Creped, greased and powdered, ladies’ wigs rose above the forehead with right-angled fortifications that extended then retreated back into the wig. Huge balls maintained in place with iron pins dangled from each side, complimented by a voluminous chignon at the back.

Hairstylists and wigmakers were unstintingly ingenious with their designs. The latter included styles called the horn of plenty; dove; sleeping dog; kite and hedgehog.

Hair scaffolding made of gauze, bolsters, flowers and feathers got so high that ladies could no longer find carriages with enough height to accommodate them. They were forced to stick their heads out of the carriage door or kneel on the floor to protect the towering constructions teetering on their heads.

Wig powdering became a sporting exercise! The hairdresser-wigmaker, armed with an enormous silk hoop, would chuck the powder in the air with all his might. The client, wrapped up in a long robe, face shoved in a cardboard cone to avoid being blinded by powder was positioned to receive the cloud of powder as it descended from the ceiling. To prevent the powder from creeping into other rooms, the event often took place on the landing, meaning that any unfortunate visitors sprinting up the stairs at the wrong time could bid a hasty retreat.

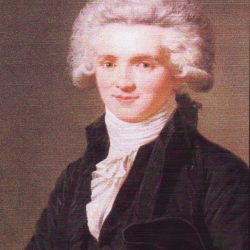

Powder was part of the military costume ritual and even persisted during the Revolution. Robespierre never left home without being suitably powdered and it was only after his Italian campaign that Bonaparte gave the trend up.

Annick Le Guérer, anthropologist, historian, writer of the sense of smell and of the perfume, has published numerous books including: Les pouvoirs de l’odeur (François Bourin 1988, Odile Jacob 2017), L’odorat, un sens en devenir (L’Harmattan, 2003), Trois histoires de nez aux origines de la psychanalyse (L’Harmattan 1999), Le parfum des origines à nos jours (Odile Jacob 2005), Histoire en parfums (Le Garde Temps 1999), Sur les routes de l’encens (Le Garde Temps 2001), Quand le parfum portait remède (Le Garde Temps 2009), L’osmothèque, si le parfum m’était conté (Le Garde Temps 2010), 100 000 ans de beauté (en collaboration, Gallimard 2011), Givaudan, une histoire séculaire dans Une Odyssée des arômes et des parfums (La Martinière 2016).

- Le poudrage: le petit chien ne semble pas apprécier…

- Cette fois c’est le chat , réfugié sur une poutre qui n’apprécie pas!

- Portrait de Robespierre en perruque poudrée

- Portrait de Robespierre en perruque poudrée

- Caricature: un petit valet obligé de soutenir l’édifice capillaire de sa maîtresse. “Quelquefois les coiffures montent insensiblement; et une révolution les fait descendre tout à coup. Il a été un temps que leur hauteur immense mettait le visage d’une femme au milieu d’elle-même: dans un autre, c’était les pieds qui occupaient cette place; les talons faisaient un piédestal, qui les tenait en l’air. Qui pourrait le croire ? Les architectes ont été souvent obligés de hausser, de baisser et d’élargir leurs portes, selon que les parures des femmes exigeaient d’eux ce changement; et les règles de leur art ont été asservies à ces fantaisies.” (Montesquieu, Lettres persanes)