Meaning in flight

01.11.2016« Mes mains toquent en vain, moi j’en peux plus! Lise, ça va bien? » What an odd sentence in French to use to introduce this topic and understandably so. Understandably so? Did we hear that right? (read the words of the first sentence phonetically and you get a different meaning from the words « Memento qu’en vingt mois, gens, peuples, plus ! Lisent, ca va bien… (did they get it?) » Lise does not refer to a bird; this whole concept is actually the language of birds.

The language of birds can be found in written language (probably in all of the latter) and has existed since Antiquity right up to the slang and meta-language created by teens. It earned its spurs with the alchemists of the Renaissance and in a variety of esoteric movements, members of whom wrote their treaties and re-read text using the sounds to reveal secret meaning: because this so-called language of birds is not based on coding or encryption, but phonetics so that you actually hear something that is at odds with what has been written. This adds another dimension to the reading process.

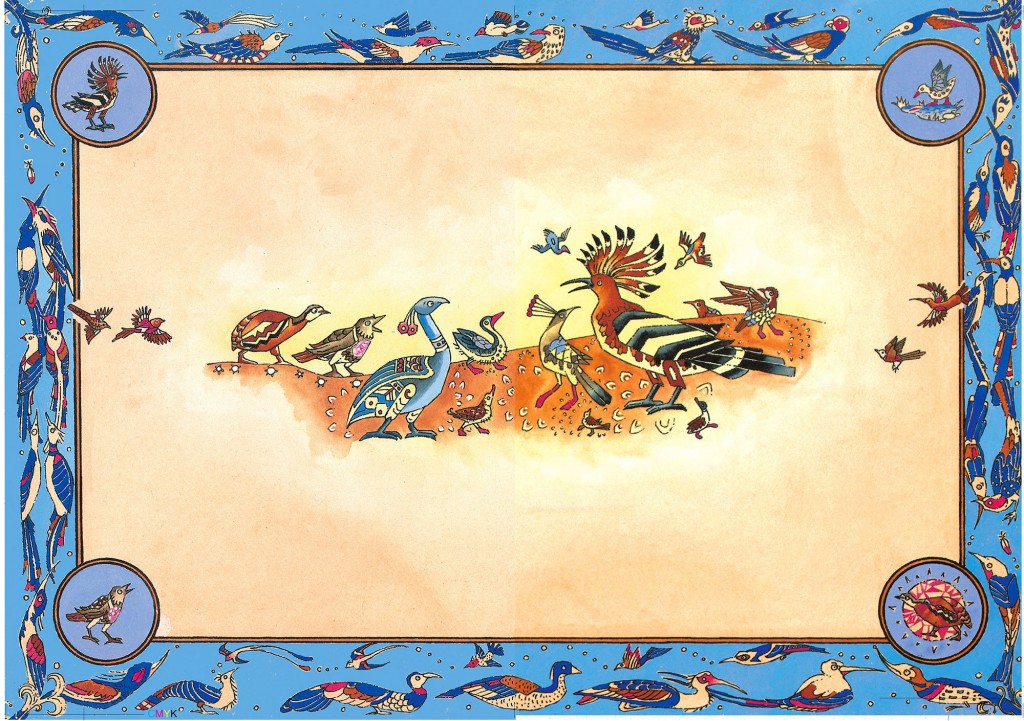

Why birds? Maybe because since time immemorial birds have symbolised the link between this shadowy world and the transparency of the skies above. This connection is ‘precieux’ and ‘essentiel’ (in french hear the words precieux = close [to the] heavens, and essentiel = essence [of the] sky) : « birds are the messengers of the gods » wrote Greek tragedian Euripides. A mythological tale relates that Jupiter compensated Tiresias’s blindness caused by his wife Juno by giving him the gift of understanding the language of the birds, a gift of supernatural foresight. Perhaps because this language gives words wings, making their real meaning take flight. Or maybe because it distorts the language of goslings spoken by the secret fraternity of cathedral builders…

But the principle remains the same. By rising above the spelling, the language toys with syllabic assonance, homonyms (identical sounds), paronymy (neighbouring sounds), euphonies (harmonious sounds), connotation, evocation of images…all of which have semantic resonance (meaning). The language can be packed with scholarship (etymology, hermetic system of symbolic correspondence between sounds, colours, ideas, people) or the technical complexity of word play: acronyms (the first letters of a series of words, UN or LOL), acrostics (first letters of each line), anagrams, inversion, charades… All to provide hidden meaning to the discerning reader.

S100C ? (est-ce cense = is it done on purpose)? Sure, but it is brilliant. Over to you to see what’s what by pinning back your ears. Many writers have tried in every language you can think of to make the language sing when spoken. Swift and James Joyce were masters at it. We should also take into account the offshoots of the language of birds. For S. Freud, C.G. Jung and J. Lacan, the key lay in psychoanalysis, by revealing the coded language of unconscious dreams that bursts to the surface via verbal slips of the tongue. The language is pushed to its limits by the French Oulipo (Workshop of Potential Literature). It abounds in teen slang, which toys with vowel deletion, contractions, jargon, acronyms, and goes global by borrowing from all languages and then deforming and recomposing new, ingenious and hilarious idioms. Finally it has become mandatory in today’s journalistic and marketing styles for catchy headlines and clever slogans.

The language of birds creates a connection: it recalls the care taken with words and signs by Desmond Knox-Leet, who once worked as part of the secret teams at Bletchley Park, and heralds the synesthetic correspondence hidden under the wings from which forthcoming articles will resonate…