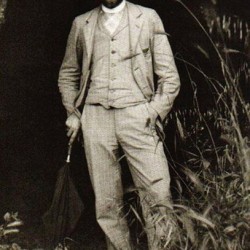

Karl Blossfeldt

04.13.2015The Botanical Anthology of Karl Blossfeldt

Elodie Morel, Sales Director for photographs at Christie’s, reflects on Karl Blossfeldt work

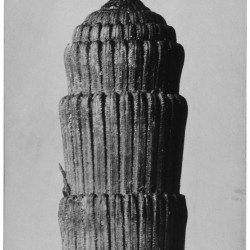

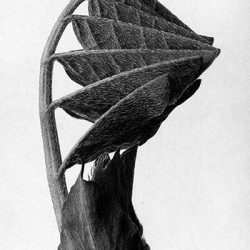

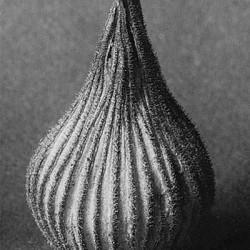

Tangled curls, pleated textures, newly-born buds, repetitive ribbing, the essence of Karl Blossfeldt’s art lies in his photographs of plants to which he dedicated his entire career to. His work was intended at first to become a ‘notebook for inspiration’ for decorative design in the 1920s – as a whole set, it holds more than six thousand photographs showing the artist’s fascination for ornamentation.

Working at the Hochschule für die Bildenden Künste (Berlin School for Decorative Arts), he undertook a long-term project – collecting, classifying and drawing plants in order to produce a unique portfolio of vegetation. In Berlin, Rome, Greece and Africa, he puts together a photographic inventory of reality and flora.

Blossfeldt’s photographical anthology reminds us of works from naturalists in past centuries but this isn’t a simple collection of dried plant life anymore. Blossfeldt sees the form of a plant and its growth as an integral universal part and pattern that can be applied to not only understanding human beings but to architecture and industrial arts. A thistle brings to mind the tympanum of a gothic church, the stalk of a horsetail – an ancient column, the coiled ends of ferns – a bishop’s crosier.

Photographic enlargement was the only way to highlight or reveal a detail, a texture, a curve, an isolated form or a symmetry. To bring to light forms and models, Karl Blossfeldt has followed a strict code during this life-time’s work, showing the taste and the patience of a man whose purpose was to make visible what he saw and to convince his viewers. He wanted to produce new creations by enabling the eyes to see these surfaces whether rough, silky or coarse-grained. Plants were always photographed on a background, neutral, black or white, to bring out their edges which would be glued or even often trimmed. He would add the Latin name of each plant at a time when scientific material was quite popular.

Calyx, maple or dogwood branches, leaves of Field Eryngo, larkspur – Blossfeldt’s teachings start with the learning of lines, by observing the proportions and the basic shapes of flora. Based on this return to origins, Karl Blossfeldt offers new forms, until now unseen, that express a rigorous beauty close to Art Nouveau and which inspired a new generation of photographers. Not only do Blossfeldt photographs seem to be the work of an ornamental pattern maker but this whole collection of images leaves us with a very simple thought – the form of nature precedes the artistic form.