Green apples and little grey cells

07.20.2018Stealing golden apples from the garden of the Hesperides was the eleventh of the twelve labours of Hercules. Putting them back would be the eleventh of twelves tasks for another Hercules who is more distinguished than this “beefcake with a low forehead animated by criminal tendencies” antique: Hercule Poirot!

The famous golden apples from the mythological story symbolically designated oranges or quinces, or perhaps even the homophony of sheep. What a concept, but these were emeralds! Set around a goblet of priceless value and probably the work of the great Benvenuto Cellini, a major artist from the Italian Renaissance. “The goblet represents a tree around which a bejewelled serpent is coiled. And the branches are laden with apples represented by a profusion of emeralds” : this is of course one of the cases set for Agatha Christie’s brilliant detective to solve.

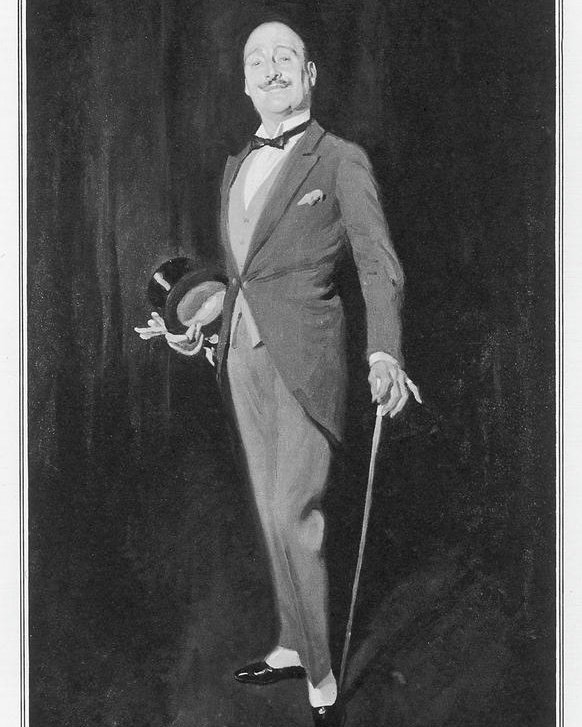

In the Twelve Labours of Hercules, a short story collection of twelve stories identical to those of the mythological tale, Hercule Poirot hopes to round off his career by solving twelve cases chosen for their links – far-fetched for a person dressed up to the nines – to the adventures of the hero from antiquity. Everything came about following the derogatory reflection by Poirot’s friend Professor Burton, a prominent figure at All Souls College in Oxford, as famously unkempt as the famed detective was immaculately dapper. He criticises him for never having spent time studying the “great classics”. “I did very well without them” responds the vain yet amenable gentleman.

A little later Poirot flicks through the story of Hercules’ adventures. He is afraid of this coarse brute. As for the Gods of mythology, “they behaved like complete delinquents. Alcoholism, debauchery, incest, rape, robbery, murder and snatching inheritances – plenty there to keep a magistrate occupied on a full time basis! No decent family life here! No order! No systems in place! Except when it comes to their crimes and offences which revealed a total absence of discipline and reasoning!”

So he goes on to solve a case that he can link to the golden apples in the garden of the Hesperides. A priceless goblet has been stolen and its owner, a top financier, wants it back. There are many leads that take the detective across the planet. The detective suspects the maid in a jiffy. By a clever final reversal, he will thwart the instinct of returning the stolen goblet under a condition that is as unexpected as it is moral in tone…

Agatha Christie toys with the vanity of her hero: “As if confessing to royal stock, the little man modestly declared: “I am Hercule Poirot.” But his actions are nonetheless generous and just; he is a good man. And although rigorous to the extreme, he is nevertheless inconsistent, since at the end of these twelve cases he does not go off to grow marrows as he had originally planned for his retirement but continues to flex his clever grey cells in plenty more adventures.