Fahrenheit 451

02.27.2017

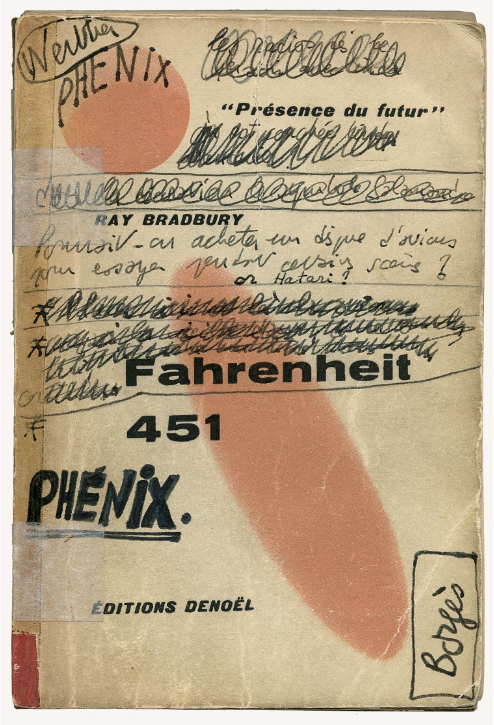

Couverture annotée par le cinéaste François Truffaut du livre Fahrenheit 451 de Ray Bradbury, éditions Denoël – (La Cinémathèque française © Succession François Truffaut)

Fahrenheit 451 is a futuristic novel by Ray Bradbury published in 1953 and adapted for film by François Truffaut in 1966 with the author’s consent. The title refers to the assumed temperature at which paper combusts. In the fictitious society in the novel, books are outlawed, hunted down and destroyed by fire.

Often referred to as a dystopian novel (the opposite of the utopian ideal) this narrative features a nightmarish society. It depicts the domestic ‘joys’ of a consumer society in which households enjoy a comfortable existence with ‘no history’. The French expression hits the mark: culture, knowledge, memory, reflection, imagination, and education provided by fiction are all banned and out of the question in this society. Books are prohibited. Firemen now have a new role – their brigades are focused on burning all books. These methodical book-burning activities are often the end result of people spilling the beans on others. This totalitarian society appears to be peaceful and ordered on the surface. But people are medicating themselves and are subsequently in too much of a bewildered state to act spontaneously, have fun and sleep. Their minds are blank. They are no longer able to think or feel anything outside the box. Everything falls within set norms and outcomes. Most of all these people no longer know how to love. It appears that this despotic society has succeeded in « sparing them of all the care of thinking and the pain of living » in the contented yet shocking words of Alexis de Tocqueville.

In this standardised society everyone falls in line with measures dictated by the authorities – lifeless consumerism with zero vigour and passion. It is imputed to reduce inequality and vanity and any subsequent disorder. To achieve this aim society must be stripped of culture to ensure this state of dull collective felicity. This political regime relies on nescience: the absence of knowledge and awareness.

Books have been replaced by TV screens which are constantly switched on, broadcasting placatory programmes and interacting with citizens – especially housewives, who behave in a coquettish and foolish manner in front of their TVs. This televisual presence encourages viewers to participate live from their sitting rooms, providing them with popularity status via nonsensical interaction. The community formed by show presenters and the viewers, whether passive or active, is called the « family ». The flat screen TVs in Truffaut’s film look just like today’s plasma screens. Caricaturally and critically, this notion seems to be ahead of its time, nodding to our current social network usage. Today an avid quest for popularity and meaning in life stems from gawping at a screen that is always switched on, eclipsing the beauty of real life beyond it.

So how can anyone fight against such ignorance without putting their own life in danger? Memory is the key. To fight is to grow. As books have been burnt as the source of all discord, along with the eradication of any opposition, all that remains is to learn a book by heart and transmit it orally until one day, society will allow the words to be printed again. In the absence of paper, the head will do. Driven by the need to protect the flower of humanity’s inheritance for future generations Fahrenheit 451 concludes with the discovery of lawful fringe communities of book-beings or « book covers » with individuals named after the title and author of a book that they can recite in full, becoming the living guarantors of its invaluable content and without which mankind would lose its humanity.