Edo art forms

04.24.2017Edo (the original name of Tokyo) also refers to a period in history (Tokugawa shogunate). Its military tradition and hereditary rule established a period of internal peace and stability and a strict political, social order. Ironically, this period spawned certain ‘refinements’ that seem at odds with its austere rules.

How amusing is it to look at the first commandment of the bakufu (shogunate or military regime) of Tokugawa Ieyasu, which began in 1603, and marked the start of the Edo era: « Neglect pleasures and focus on unrewarding tasks », and compare it to the following preface written in 1665 by Asai Ryôki in Ukiyo Monogatari (Tales of the Floating World) : « […] to live in the moment, devoting yourself totally to contemplating the moon, snow, cherry blossom, maple leaves and autumn leaves; to revel in wine, women and song; to stop poverty from grinding you down or showing in your face in favour of drifting along like a calabash (gourd) in a river, that’s ukiyo. »

The Heian era (794-1185), a time a peace throughout the Empire and at court, was the classical age for the arts, and poetry in particular. The periods that followed though were marked by feudal wars. The Edo era brought peace once more, initially by establishing a stronghold at Edo – quite some distance away from the administrative capital Kyoto, a place buzzing with intrigue. It wasn’t long before all the daimyô (feudal lords) were summoned to live there every other year, sometimes leaving their families as hostages. The country isolated itself totally from the rest of the world. Maps were prohibited and roads were left in a damaged state to prevent any rebellion and movement was controlled by taxes. Social hierarchy was the absolute backbone of the regime. The nobility lived in luxury, committed to their ruler; the farming peasants and craftsmen, who were encouraged to be virtuous and to work hard, were heavily taxed but respected. Merchants were close to the bottom of the social order but necessary. Even worse were the artists, poets and actors, who were marginalised within the lower classes. Finally a significant number of warriors now found their knowledge bank of war-related activities useless at the service of an enslaved nobility. Customs were strictly codified; speech monitored; etiquette essential and censorship was rife.

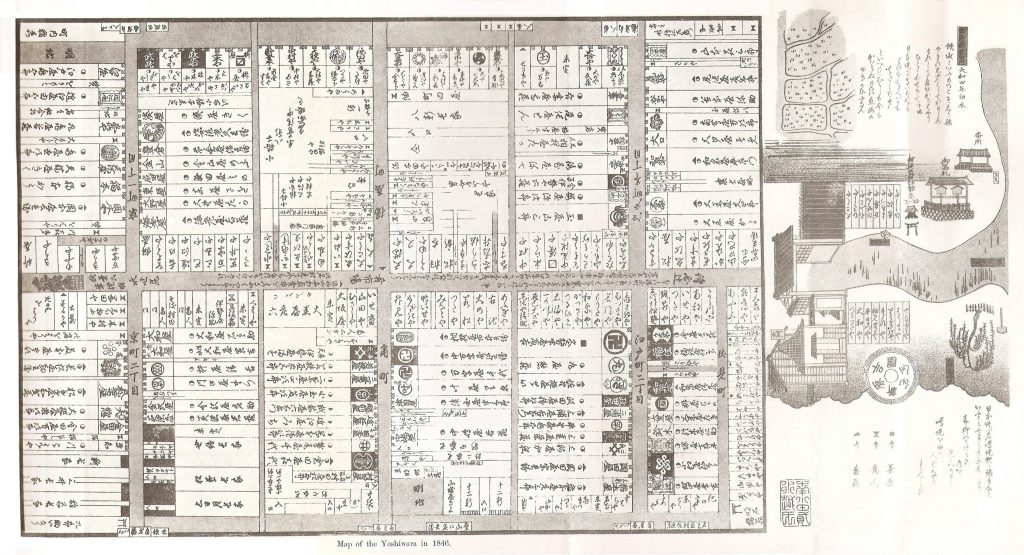

But this law-abiding bourgeoisie was enriched by the comings and goings and great pomp of the aristocracy who lived the high life during the Edo era, despite society’s obligations. Prosperity led to entertainment initiatives, including the birth of Kabuki theatre. Moreover, many Samurai who were required to observe bushidô (code of moral principles) were deprived of their martial role. They represented 8% of the entire population and inhabited two thirds of Edo town. They were reorientated towards traditional arts that did not go against their way of life but helped to assuage their rarely used power. Finally, as Edo boomed, so did the number of single men looking for distractions. And so the town spawned a licensed pleasure quarter called Yoshiwara, a red-light/theatre district inhabited by artists, courtesans and mediators who rubbed shoulders with a well off elite who did not have images of these illicit activities. And so « ukiyo-e » (images of the floating world) were painted depicting a universe initially experienced second-hand by the rest of the population through stories and images; a narrative that was a long way from the art painted by Kanô school artists who worked for the nobility. Some of the great masters of ukiyo-e included Kitagawa Outamaro (1753-1806), Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) and Utagawa Hiroshige) (1797-1858). Artists and publishers were subjected to censorship, especially when these floating images touched on shunga (spring pictures).

And this is how, during an era marked by a repressive political regime, the capital Edo – future Tokyo (1868) – was a place of forbidden art that celebrated idleness and pleasure whilst the three traditional art forms (tea ceremony, kôdô and kadô) gradually gained popularity amongst the affluent bourgeoisie who appropriated aristocratic rituals.

diptyque is opening a new boutique in Tokyo in the Ginza Six shopping mall.