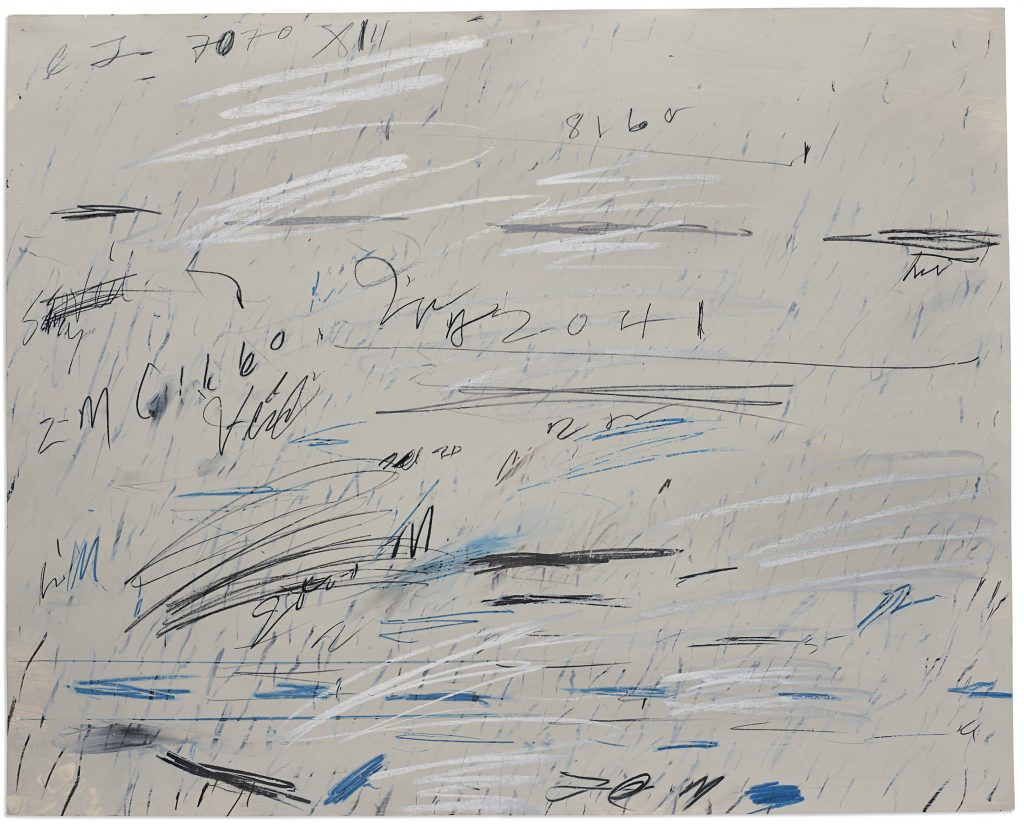

Cy Twombly

04.21.2017

Untitled, de Cy Twombly (1928-2011). Huile, mine de plomb et crayon gras sur papier 70 x 87.5 cm. (27½ x 34½ in.) Réalisé à Rome en juillet 1970.

Cy Twombly, by Paul Nyzam

Cy Twombly’s work raises the question of language right from the get-go. What exactly are we looking at? Splatters, illegible scribbles, ungainly lines criss-crossing canvases in an apparently random way, childlike graffiti, crossings-out – sometimes left as they are, sometimes partially erased – numbers and words (names, more often than not) and trickles of paint. What to make of it all? How can you define this rather unusual way of painting? Is it the work of an artist or something else? When push comes to shove, shouldn’t we say, as art historian Simon Schama remarked “Twombly ought to be (if it isn’t already) a verb, as in Twombly, v. tr. – to hover thoughtfully over a surface, tracing glyphs and graphs of mischievous suggestiveness, periodically touching down amidst discharges of passionate intensity”?

We ponder the man for a moment. Twombly was born in 1928 in Virginia, a rural state far away from the hustle and bustle of towns on the coast. A student at Black Mountain College – where he rubbed shoulders with John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Franz Kline and Robert Motherwell – he was awarded a scholarship that led to his first trip to Italy in 1952-1953. Mediterranean culture – the endless richness of its history and architecture, its poetry, the light there unlike any other – had a profound impact on him that would last his whole life long. After a short trip back to the USA in 1954, when he worked as cryptographer for the US Army (should we regard this episode in his life when he was involved in coding language as a key to reading his love of dissimulation and secrets in his art?), Twombly finally settled in Rome in 1957 and married a rich Italian aristocrat.

His art then blossomed freely, far from the dominant American movements of that time – abstract expressionism of the Fifties, Pop art and minimalism in the following decade -, but displayed classical erudition on the other hand, whether mythological in nature (Orpheus, Pan, Apollo, Patroclus and Achilles are the heroes in his work) or pictorial (numerous references to Raphael, Poussin and David). As time passed by, the palette of colours drew increasingly from the chromatic repertoire of his beloved Mediterranean with the radiant reds sometimes enjoyed during the summer in Gaeta on the Tyrrhenian coast where the artist had a workshop; and the dazzling off-whites of lime-washed homes.

The distinctive nature of his art is echoed in his sculpture, created from common materials (cardboard, wood, plaster, paper, metal rods) and painted uniformly in white, their hieratic majesty being reminiscent of Etruscan or Egyptian sculptural forms. This lack of flashiness reveals that fundamentally Twombly’s raw material, his materia prima, was actually history itself; its depth, its breadth, its clout – all of which he brings to play in his art. When he painted Herodias, Ode to the Psyche or the Nine Discourses of Commodus, the artist does not represent anything in the usual sense of the term; instead he brings the energy and the presence of these historical or mythological figures to the canvas. Art that is both painting and literature, Twombly’s work would remain hush-hush for a long time, because it was hard to access it beyond a circle of learned advocates, including one of the most fervent, Roland Barthes. The current, and rather magnificent, retrospective at the Pompidou Centre provides everyone with the opportunity to appreciate the significance and grace of this artist’s work.

Paul Nyzam is a Contemporary Art expert at Christie’s.