Aby Warburg’s concept of artistic survival

06.09.2017Aby Warburg’s concept of artistic survival, by Soko Phay

Who would have thought that Aby Warburg’s central concept of « the afterlife/survival », one of the most productive theories in the anthropological history of images because it questions memory in work and the traces of one culture in another –, sprang from a clash with otherness? It was during his travels in New Mexico (1895-1896) when he met Hopi Indians that he experienced this otherness. His encounter with heterotopy and these « counter-spaces »[1] made him aware in retrospect of the principles underlying the history of Western art: « Without studying their primitive culture, he said, I would never have been able to put forward a comprehensive foundation for the psychology of the Renaissance[2] ».

Although he did not participate in person, Warburg became interested in the religious Snake Dance performed by the Hopis that involved priests dancing with poisonous snakes in their mouths. Spectacular to watch and as jerky a flash of lightning, the snake is the interceptor between the priests and underworld where the rain-gods live. Because it sheds its skin it symbolises change, a kind of « death-renaissance » where nothing comes to an end even if everything disappears. From this ritual involving a radically different place where life continues beyond loss, Warburg invented a new way of thinking about images and their paradoxical nature via the notion of survival. Even if the German word Nachleben includes the verb for life (leben), it also includes the word for afterwards (nach), as if to emphasise the return of images. In this respect, the Renaissance does not revive Antiquity because it has not been expunged. Survival is a dynamic force from the past that throws a spanner in the works and questions current history.

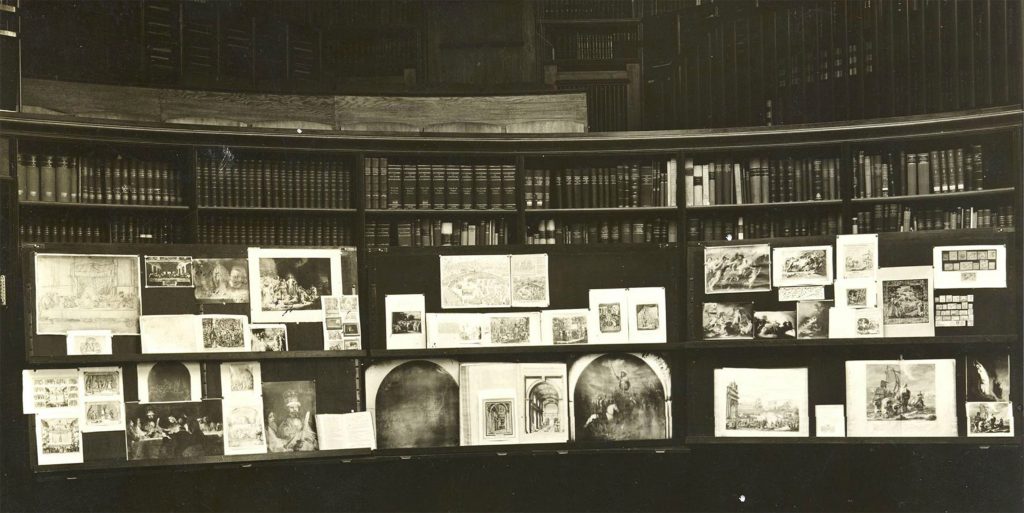

At the start of Warburg’s project, Mnemosyne Atlas, (a great compendium of images destined to make the survival and migration of expressive forms visible) Philippe-Alain Michaud said that the latter used procedures of « montage-collision that brought together masterpieces of Florentine Renaissance art and Indian culture to turn the distance in space into a metaphor for an upsurge of the past, a trip into an image of anamnesis[3]. » By assembling this Dionysian art, Warburg puts the spotlight on dialectical thought processes and anachronistic poetry as latent senses. And because they carry singularities within themselves, little glimmers of truth as fragile and as « fleeting as fireflies[4] », as Georges Didi-Huberman would say, surviving images subsequently contain sources of resistance within themselves.

Soko Phay is an historian and theorician of art, teaching in the plastic arts department of the University of Paris 8 and at EHESS. She just published Les vertiges du miroir dans l’art contemporain, Les Presses du réel.

[1] Michel Foucault, Le Corps utopique, Les Hétérotopies, presentation by Daniel Defert, Paris, Editions Lignes, 2009, p. 24.

[2] Quoted by Georges Didi-Huberman, L’image survivante. Histoire de l’art et temps des fantômes selon Aby Warburg, Paris, Minuit, 2002, p. 356.

[3] Sacha Zilberfarb, « Le peuple des images. Entretien avec Philippe-Alain Michaud », Vacarme, 1/2002 (n°18), p. 80.

[4] Georges Didi-Huberman, Survivance des lucioles, Paris, Minuit, 2009, p. 68.